3D imaging tool helps decipher complex social behaviors in animal models

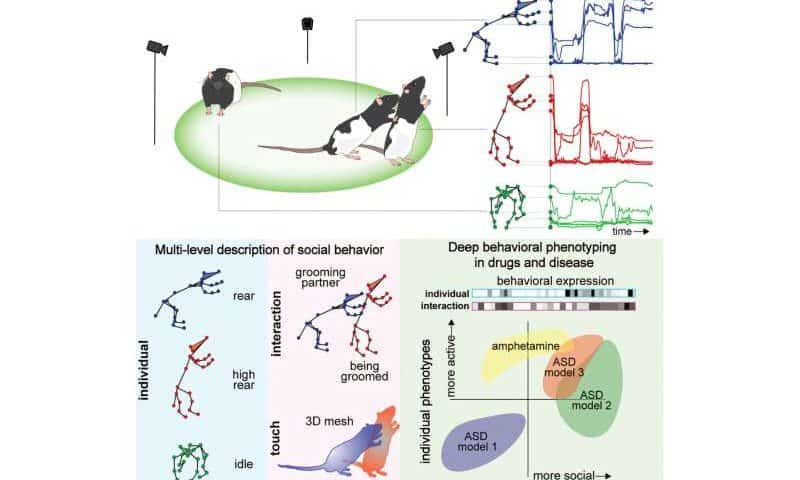

Biomedical engineers at Duke University have developed a 3D imaging method to precisely map and categorize the social behavior of animals. By quantitatively measuring the movements, interactions, and body contacts between rodents, the scientists were able to reveal for the first time how several different genetic forms of autism affected social behavior in rats.

The tool opens the door to studying new classes of neuropsychiatric disorders in lab animals. The study is published in the journal Cell.

When it comes to piecing together the inner workings of the brain, neuroscientists have an ever-evolving arsenal of tools at their disposal. High-resolution imaging modalities such as calcium imaging can track when and where neurons fire, while CRISPR-based techniques have enabled researchers to precisely manipulate neuronal activation. These advancements have helped decipher complex activity within the brain, but efforts to track how brain activity affects movement and behavior haven’t kept pace.

“Despite movement and behavior being the principal outputs of the brain, tools to quantitatively measure and track that output were almost an afterthought. If you can’t quantify behavior precisely and comprehensively, you’re not going to get an accurate picture of how disease states or therapeutics affect behavior and movement,” says Timothy Dunn, assistant professor of biomedical engineering.

Researchers had traditionally relied on primitive methods to track behavior in animal models, which involved either manually watching and scoring specific behaviors, like sitting or walking, or using simple imaging and computational approaches to measure the position of the animal over time.

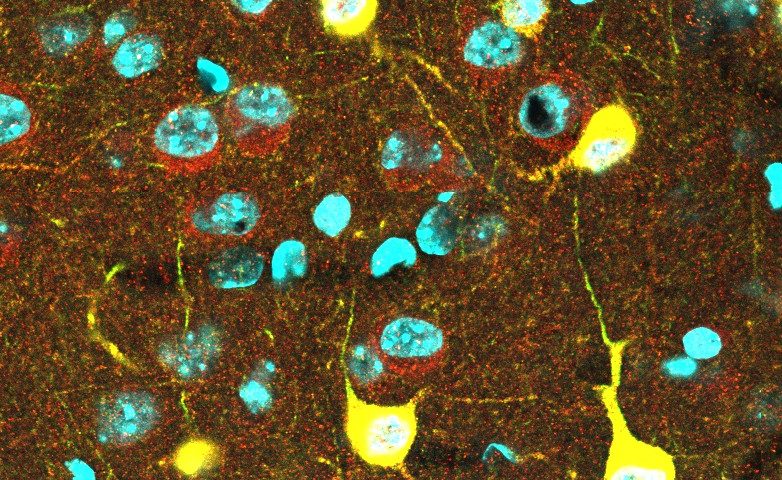

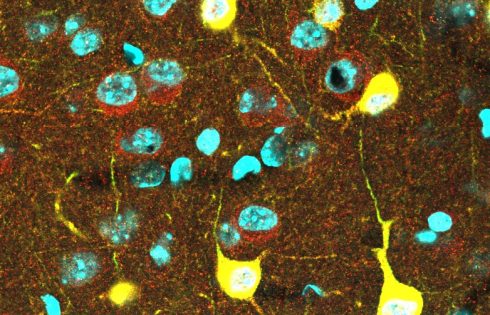

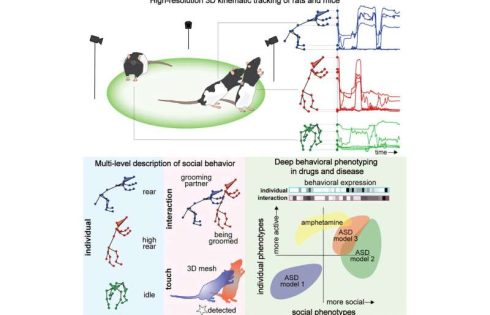

To address this bottleneck, Dunn and his team developed DANNCE, or 3-Dimensional Aligned Neural Network for Computational Ethology, in 2021. Using videos of freely moving rats, the team trained machine-learning algorithms and neural networks to identify and map the precise 3D locations of the body joints on the animals. Researchers could then relate these measurements to data collected from brain recording technologies to examine links between neuronal activity and specific behaviors.

Now, Dunn, graduate student Tianqing Li, and their team have broadened their work with DANNCE to create social-DANNCE, or s-DANNCE, a platform that can map social behavior between animals.

“Being able to track social movements is difficult,” explained Dunn. “Computer vision can’t easily separate and track each animal because they are often on top of each other and look alike. It’s also hard to distinguish individual behavior from social behavior, as many of these interactions can be very subtle.”

Building off the approach they pioneered in DANNCE, the team recorded videos of groups of two to three rats freely interacting in a controlled recording space. These videos were analyzed by a neural network, which was trained to track the movements of the individual animals.

By mapping these movements into 3D models of the animal’s joints, the researchers could identify recurring types of movements, which allowed them to sort and classify individual behaviors, like grooming, and social interactions, like chasing, sniffing or fighting.

“We showed that rat interactions can be separated into hundreds of different social behaviors that can be expressed at different levels,” said Dunn. “Once these interactions are identified, we have new quantitative units that we can use to describe how social interactions change during models of disease or when testing drugs.”

To validate s-DANNCE, Dunn and his collaborators used their models to map and identify behavioral changes of rats who received amphetamine, a stimulant that triggers noted behavioral changes in humans. Beyond inducing hyperactivity into the rats, the drug also disrupted how the animals behaved together and altered where and how they touched each other.

The team also tested their model in different genetic models of autism, where they were able to automatically detect how certain models reduced or increased specific types of social behaviors and patterns of social touch.

The team has made the s-DANNCE platform and a data set of more than 150 million 3D behavioral samples freely available for researchers to download.

“Many areas of neuroscience have been hamstrung by the lack of precise, objective, and reproducible descriptions of social behaviors, and our tool provides a solution to this long-standing problem,” said Dunn. “We hope that this technology and the large library of social interactions we have cataloged will help facilitate new studies connecting social behaviors with the brain and mechanisms of neuropsychiatric disorders.”