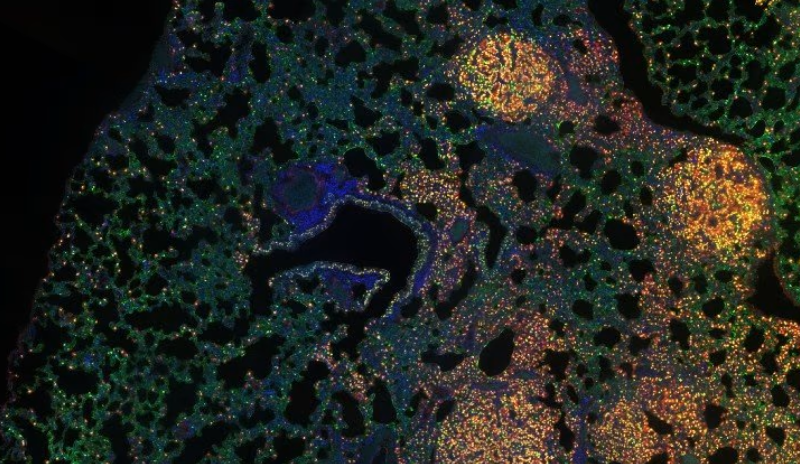

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) get a bad rap. The protective, gel-like complex surrounding tumors have been thought to be a no-go for drugs and are known to enforce treatment resistance. But surprising new research suggests that not all CAFs are created equal.

The research shows CAFs have major differences in characteristics, which is why it isn’t a good idea to wipe them out in efforts to slow tumor growth. In fact, Lily Remsing Rix and her colleagues at Moffitt Cancer Center found that CAFs can either promote or suppress drug resistance in different types of lung cancer cells. In lung cancer cells with EGFR mutations, the CAFs secreted proteins that alleviate drug resistance, making them sensitive to kinase inhibitor osimertinib.

Researchers found that CAFs have varying effects on tumor cells. They discovered that CAFs effects on tumor cells were based on both the type of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and also the drug being tested. For example, CAFs spurned resistance to two different MEK inhibitors in NSCLC cell lines with a mutant KRAS protein. On the flip side, the fibroblasts sensitized the cancer cells with a mutant EGFR protein to EGFR inhibiters. Normal lung associated fibroblasts never sensitized cells to treatment, which suggests it is CAFs specifically that secrete a factor that induces different responses to treatment.

Moffitt researchers found the results by comparing CAFs to normal fibroblasts, trying to figure out what produces the different effects. They found that CAFs had differences in the levels of secreted proteins involved in the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling pathway, a pathway that is involved in all cell growth and death. CAFs produced higher levels of IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs), inhibiting IGF signaling and resulting in lower levels of IGFs. Further analysis proved that IGFBPs are what sensitized the lung cancer cells to EGFR inhibitor treatments, whereas IGF proteins caused resistance to the same treatment.

Two proteins, IGF1R and FAK, both part of the IGFBP signaling pathway, tell the whole story. Drugs that block these proteins’ activity sensitize mutant EGFR lung cancer cells to EGFR inhibitors, giving insight into a combination treatment approach. According to lead study author Remsing Rix, the results “add to the growing evidence that eliminating cancer-associated fibroblasts in an undifferentiated way may be detrimental to cancer therapy.”

The researchers copied the drug-sensitizing effects of CAFs in mice with tumors by combining small-molecule inhibitors of IGF1R and FAK. The findings represent a new drug-targeting strategy. Corresponding study author Uwe Rix, Ph.D., said that “understanding these mechanisms can indeed have therapeutic implications, as the CAFs can sometimes show us the way to best kill cancer cells.”

Fibroblasts in other types of cancer are an attractive target. In January, researchers found that blocking expression of a protein called PKN2 changed the behavior of fibroblasts. They suggested that drugs that target this protein could be part of a combination study for pancreatic cancer. In a 3D cell culture model, deletion of the protein suppressed the ability of pancreatic fibroblast cells to invade when co-cultured with pancreatic cancer cells, suggesting that altered CAFs are less mobile and invasive. Without the protein, CAFs became inflammatory, which could promote more aggressive tumor growth or could theoretically make tumors more responsive to immunotherapy.