Genetic mutations can lead to abnormal DNA transcription and, ultimately, cancer. Now, scientists at the University of Michigan have described a key nexus that several cancer-promoting genes depend on to drive prostate cancer, offering what they say could be a novel approach to treating the disease.

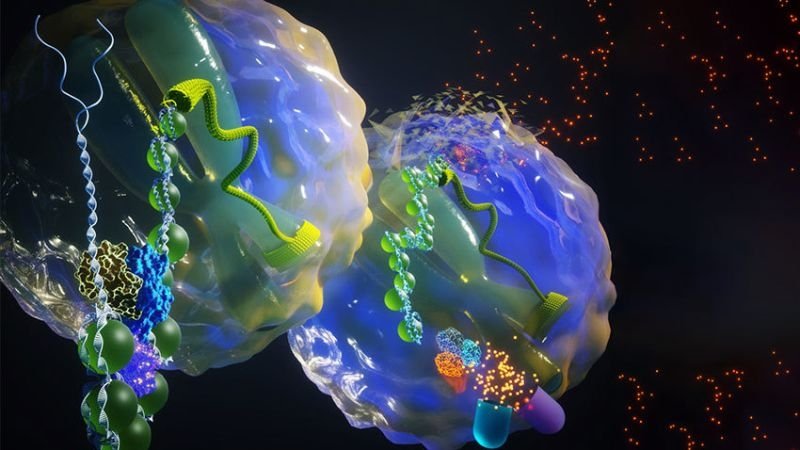

The hub is a protein complex called SWI/SNF, which rearranges the way DNA is packaged to mediate gene expression. A subunit of the chromatin remodeling complex provides problematic transcription factors access to enhancer elements that boost the expression of oncogenes in prostate cancer.

In a new study published in Nature, the team worked with Dovetail Genomics to test a SWI/SNF protein degrader designed by India’s Aurigene Discovery Technologies. The small-molecule drug, dubbed AU-15330, significantly inhibited tumor growth in several mouse models of prostate cancer.

In human cells, DNA is tightly wrapped in chromatin, which acts as a barrier to DNA-related biological processes. Chromatin remodeling complexes like SWI/SNF can change how DNA is packaged, opening up chromatin while allowing genes to be activated. Cancers are particularly dependent on the protein complex for their aberrant growth.

“Normal cells can survive with default levels of gene transcription, but cancer cells are particularly addicted to these enhancer regions. They need access to these enhancers to jack up the expression of oncogenic targets,” the study’s senior author, Arul Chinnaiyan, M.D., Ph.D., explained in a statement.

For their study, the researchers developed AU-15330 as a proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) degrader of the key SWI/SNF subunits SMARCA2 (BRM) and SMARCA4 (BRG1), which are required for the complex’s functions.

The researchers found prostate cancer cells that were driven by the androgen receptor or FOXA1 are the most sensitive to AU-15330. In these cell lines, AU-15330 rapidly degraded SWI/SNF, blocked the growth of the cells and induced programmed cell death. By contrast, the drug had no anti-growth effect on benign or noncancerous prostate cells.

Degradation of SWI/SNF with AU-15330 appeared to have kept chromatin compacted, or closed, to cancer-driving transcription factors, including the androgen receptor, FOXA1, ERG and MYC, the researchers found. What’s more, the drug markedly decreased expression of the transcripts themselves to 40% to 60% of their baseline levels and disabled their looping interactions with enhancer elements.

In a mouse model bearing prostate cancer tumors that were resistant to Pfizer and Astellas’ anti-androgen med Xtandi, treatment with AU-15330 significantly shrunk tumors in over 20% of animals. Further, the PROTAC degrader worked better when used in combination with Xtandi as the cocktail led to cancer regression in all rodents, the team reported. No significant change in body weight or any other signs of toxicity in essential organs were observed.

Genes encoding subunits of the SWI/SNF complex have been found to be mutated in 20% to 25% of human cancers. In SWI/SNF-mutated tumors, the residual functioning complex is thought to be driving oncogenic processes. Some cancers that lack SWI/SNF mutations were found to be vulnerable to inhibition of certain SWI/SNF subunits.

The complex’s role in gene expression has attracted interest in cancer research. A 2018 Nature Cell Biology study led by scientists at Harvard Medical School found that inhibiting the BRD9 subunit of a final form of SWI/SNF suppressed synovial sarcoma and malignant rhabdoid tumors.

James Bradner, M.D., president of the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research (NIBR), was a co-author in that study. Several other authors come from Foghorn Therapeutics, which just penned a deal with Eli Lilly potentially worth $1.38 billion to work on drugs against cancers with mutations in BRG1.

In a 2020 study published in the journal Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, a team of NIBR scientists found that the SWI/SNF complex is essential for uveal melanoma, suggesting it could be targeted for the rare eye cancer.

As for AU-15330, the University of Michigan team believes the PROTAC degrader holds promise for treating prostate cancers driven by multiple genetic mutations, which altogether represent up to 90% of cases of the disease. Plus, it opens the possibility of blocking SWI/SNF as a therapeutic approach to tackle other cancers that are addicted to oncogenic enhancers, the researchers said.