A new type of antibiotic for treatment of urinary tract infections in women could also work against gonorrhea infections, a new study finds. This could put the medication, called gepotidacin, on track to become the first new antibiotic for gonorrhea since the 1990s.

“Gepotidacin is a novel oral antibacterial treatment with the potential to become an alternative option for the treatment of gonococcal infections, supported by an acceptable safety and tolerability profile,” the researchers wrote in the study published Monday in The Lancet, adding that the drug “could mark a meaningful advancement in patient care.”

As an antibiotic, gepotidacin works by inhibiting bacteria from replicating in the body. In March, it was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat uncomplicated urinary tract infections in women and girls ages 12 and older. Recurrent UTIs have become a bigger problem as the bacteria that cause them have become more resistant to the antibiotics available to treat them.

Now, there is new hope that gepotidacin may help fight drug-resistant gonorrhea.

“The big takeaway is that having additional treatment options for gonorrhea is fantastic,” said Dr. Jason Zucker, an infectious disease and sexually transmitted infections expert and assistant professor of medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, who was not involved in the new study.

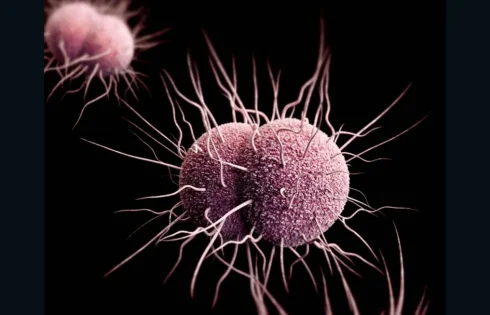

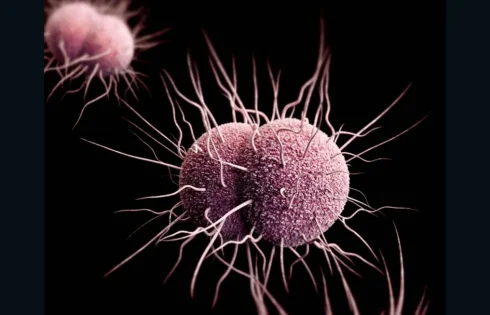

Effective treatments for gonorrhea have become increasingly limited in recent years due to the global rise of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the bacteria that cause gonorrhea, rendering many previously used first-line antibiotics ineffective.

The current standard of care involves an intramuscular injection of the antibiotic ceftriaxone, which requires a visit to a care facility.

A key benefit of gepotidacin is that it would not involve an injection at the doctor’s office, which could make treating gonorrhea more convenient for patients, Zucker said.

“Right now, patients come in, especially if they are not having symptoms, if they test positive, we have to ask them to come back. For some people, that’s not so easy,” he said. “So obviously, the ability to have the pharmacy send treatment to their house, or have them be able to pick it up, would really make things a lot easier for people and reduce the number of doctor visits they have, especially if they have jobs where they don’t have a lot of time off.”

Gonorrhea can lead to serious health problems if left untreated, and though rare, can even spread to the blood or joints. Among women, untreated gonorrhea can cause an infection of the reproductive organs called pelvic inflammatory disease, which can lead to a greater risk of pregnancy complications and infertility. In men, gonorrhea also can lead to infertility in rare cases.

In the United States, gonorrhea and other sexually transmitted infections or STIs have become more common. Reported cases of three nationally notifiable STIs – chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis – were up 90% in the US in 2023 compared with about two decades prior in 2004, according to data released last year by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 2.4 million cases of STIs were reported in 2023 nationally.

The Phase 3 trial, conducted between October 2019 and October 2023, included more than 600 people ages 12 and older who were diagnosed with gonorrhea in the urogenital area across six countries: Australia, Germany, Mexico, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The study was funded by the pharmaceutical company GSK, which developed the antibiotic, and the development of gepotidacin was funded in part with federal funds from the US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, according to GSK.

About half of the study participants were treated with a gepotidacin regimen of two oral doses administered about 10 to 12 hours apart, at 3,000-milligrams per dose. The other participants were provided with the current standard treatment of administering a single dose of the antibiotic ceftriaxone as an injection paired with orally taking the antibiotic azithromycin.

The trial data, which is being presented at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases conference, showed that gepotidacin was as effective as the current leading combination treatment, and was also effective against treatment-resistant infections, which occur when strains of gonorrhea are resistant to currently used antibiotics.

The gonorrhea infections were cured among 92.6% of the study participants who were administered gepotidacin compared with 91.2% of the study participants who were treated with ceftriaxone plus azithromycin.

Among the 7.4% of participants in the gepotidacin group who were not successfully treated, they all were due to missing data, according to GSK, which added that “in participants with complete data, there was no bacterial persistence at the urogenital body site.”

While the study primarily assessed gepotidacin as a treatment for urogenital gonorrhea, some participants with rectal and throat infections were evaluated. Of those with complete data, the study showed that it was more difficult to treat gonorrhea in the throat compared with other body sites, as 14 out of 16 people with throat gonorrhea and complete data – 88% – were successfully treated.

The researchers wrote that the prevalence of throat infections “warrants further investigation” in a larger group of participants, as does studying the efficacy of geptodiacin in the treatment of gonorrhea in the throat.

“Pharyngeal gonorrhea is notoriously harder to treat and plays a key role in silent transmission and resistance development, so having reliable oral options at all anatomical sites is critical,” Zucker, said.

The international team of researchers found no life-threatening nor fatal side effects associated with either treatment approach used in the study, but the gepotidacin group had higher rates of side effects compared with the ceftriaxone-plus-azithromycin group, which were mostly gastrointestinal, such as diarrhea and nausea, and almost all were mild or moderate, according to the study.

“One of the challenges is that a lot of oral antibiotics have GI side effects,” Zucker said.

The researchers noted that it will be important to investigate the efficacy of gepotidacin for treating gonorrhea in groups not primarily represented in the study especially women and Black and Brown communities, as 92% of participants in the study were men, 74% were White and 71% were men who have sex with men.

If gepotidacin is approved for the treatment of gonorrhea in the United States, “the price will be disclosed when the product will be supplied in a market. Our approach would be for it to reflect the value and outcomes they bring to patients, providers and payers while being sensitive to market and societal expectations,” according to a GSK spokesperson.

Bluejepa, the brand name for the version of gepotidacin approved in the United States to treat UTIs, is expected to be available in the second half of 2025.

The new study was “very well-done” with “rigorous data,” and having more options to treat gonorrhea is critical for slowing down the bacteria’s drug resistance, said Dr. Jeffrey Klausner, a clinical professor of public health at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine in Los Angeles, who was not involved in the trial.

“The more options doctors have to treat gonorrhea means that they do not have to use the same drug over and over again, which is a recipe for disaster and more resistance. We know that using the same drug over and over again leads to drug resistance,” Klausner said in the email. “If gepotidacin is approved and recommended for gonorrhea treatment, that is a true advance and will greatly help our efforts to slow down drug resistance in gonorrhea.”

In the study, researchers noted that using gepotidacin to treat gonorrhea as an oral treatment option, not an injection, may be more efficient and reduces the risk of persistent, drug-resistant infections.

Yet there is some concern that strains of gonorrhea may eventually develop resistance to gepotidacin, according to a comment paper accompanying the new study in The Lancet.

“In our opinion, N gonorrhoeae will also develop gepotidacin resistance when the selective pressure increases and where compliance to the dual-dose regimen is suboptimal,” Magnus Unemo of Örebro University in Sweden and Teodora Wi of the World Health Organization in Switzerland wrote in the paper.

“Due to the inherent ability of gonococci to develop resistance, difficulties in increasing the gepotidacin dose due to adverse events, and the lack of other treatment options, preclinical and clinical development of additional gonorrhoea treatments remains important,” they wrote. “In conclusion, gepotidacin is promising for the treatment of gonorrhoea, but the challenges to retain gonorrhoea as a treatable infection will continue.”