‘Magic carpet’ guides cells to self-organize in 3D

During morphogenesis—the process by which living organisms take shape—cells collectively position themselves in specific ways, leading to the development of tissues and organs. Being able to recreate aspects of these processes in vitro would be a huge step forward in the field of tissue engineering.

Now, a team of researchers at Yale has created a cell-driven environment, paving the way toward realizing morphogenesis in the laboratory—an advance that could lead to innovations in tissue regeneration, disease models, wound dressings, hygiene products, and other applications.

The results are published in Advanced Materials.

Prof. Yimin Luo, who led the study, explains that in living organisms, cells collectively align themselves to create the microstructures in our bodies, and then these microstructures align to create larger structures.

“Unfortunately, it’s very difficult to reproduce structures like this in a petri dish because the petri dish has no order,” said Luo, assistant professor of mechanical engineering. “You can’t manipulate where you want them to align. It’s quite difficult to get them to align collectively.”

The Luo lab, though, figured out a way to get the cells to collectively align in both 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional environments, and control the force generation process of the cells on the engineered tissue.

While scientists have previously managed to do so in 2D environments, creating a 3D environment for cells has been a challenge. Luo chalks that up to “two things that are at odds with each other.” On the one hand, you can create an environment with “rails”—structures to guide the cells into assembly, a method that researchers have used previously. But that restricts the cells to 2-dimensional movements.

“So you want something to guide the assembly, but then also decouple it from what’s been assembled,” she said. “And it turned out that it’s really difficult to do in 3D.”

To that end, Luo and her research team created what she calls a “magic carpet,” that is, they fabricated a self-organizing, cell-laden environment made from liquid crystal-templated hydrogel fibers and biodegradable collagen.

They also used a photopatterning system that they designed and built in the Luo laboratory. Photopatterning is a technique traditionally used to create specific patterns of liquid crystal mesogens—and, by extension, hydrogel fibers—but not cells directly.

However, researchers can indirectly influence cell alignment by using photopatterning to guide the alignment of the hydrogel fibers (the “magic carpet” the cells sit on). This alignment can propagate into the 3D, thereby enabling the formation of patterned, tissue-like structures.

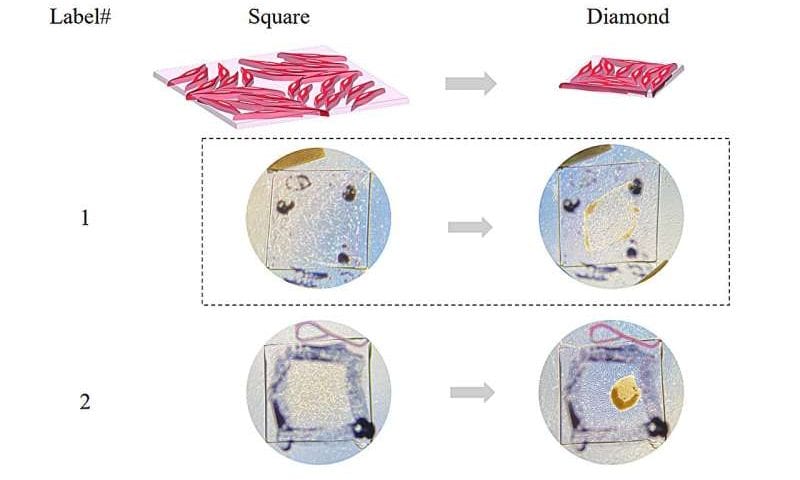

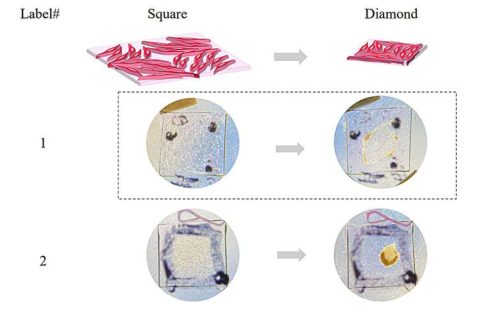

The approach allowed them to program the collective forces exerted by the cells, resulting in predefined macroscopic shape changes in the cell-laden matrix. For instance, Luo and her team were able to program the collective alignment of cells to shape the collagen matrix into a square, and then transition that to the shape of a diamond.

“So we thought that this might be the first step to self-actuating artificial tissues,” Luo said.

By demonstrating precise control of collective cell orientation, the Luo lab has shown that this very complex environment and the bio-chemo-mechanical dynamics of the cells that inhabit it can be captured in vitro.

Further, the method they developed is accessible, cost-effective, and versatile. That means it can be readily adopted by laboratories in multiple disciplines, paving the way for numerous innovations in medicine and other fields.