After success with weight loss GLP-1 drugs, IBX patients face high costs after insurer drops coverage for obesity

When her primary care doctor mentioned a new kind of medication for weight loss, Taegan Byers was cautiously optimistic.

She’d been struggling with weight gain ever since getting diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome as a teenager. She then developed prediabetes, high blood pressure and cholesterol, asthma and depression.

Byers, now 22, had tried all kinds of different methods to lose weight, through exercise and nutrition only, or drugs that suppressed appetite or insulin resistance. Nothing made much of a difference.

“I would maybe lose a few pounds and it just was so discouraging,” Byers said. “Like, what’s the point of continuing to go to the gym, what’s the point of continuing to eat healthy, and nothing’s happening, and I still feel like crap.”

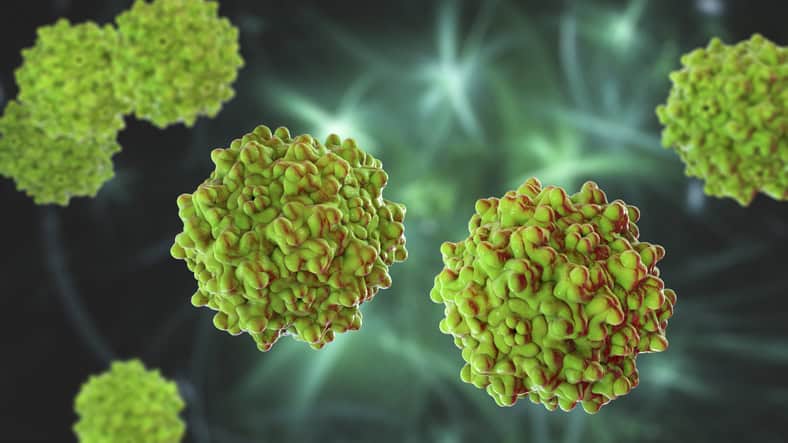

But her doctor said this new option was different. So she started injecting herself once a day with liraglutide, a type of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1) medication.

“And immediately, there was just a complete shift in my energy, and the response was great. I lost 20 pounds in two weeks,” Byers said. “I was just eating healthier, I was exercising, it was like a switch just flipped.”

That was nearly four years ago. Byers eventually switched to Wegovy, a GLP-1 medication recommended for obesity and weight loss, and has since lost 100 pounds. Most of her chronic health conditions have resolved, and her mental health has improved drastically.

“I can confidently say it’s changed my life,” she said. “I know it’s not a one-size-fits-all, but it definitely worked for me.”

Now, Byers said she fears what her treatment plan and future will look like after her health insurer, Independence Blue Cross (IBX), announced it would restrict coverage for GLP-1 and other weight loss medications beginning Jan. 1, citing the high costs of the drugs.

Uncertain future for GLP-1 users as insurance limit reimbursements

Byers lives in Michigan, but gets health insurance through an employer based in Pennsylvania.

Patients can still get coverage if they have a diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease or sleep apnea, but not if they have obesity only or for weight loss generally. They may face paying the full pharmaceutical sticker price of these drugs out of pocket, which could be as high as $1,350 a month.

“We know how much we pay into premiums and our deductibles, and at the end of the day, this is just a really selfish decision on their part because people are going to suffer from it,” Byers said.

IBX joined other major insurers like Kaiser Permanente, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, Mass Health, North Carolina’s State Health Plan and others in restricting or dropping coverage for GLP-1 medications.

Some insurers in Pennsylvania and elsewhere never covered the drugs for obesity or weight loss only.

In a Nov. 1 memo to plan members, IBX officials stated that coverage for these high-cost drugs could drive up premiums for everyone, not just people taking the medications.

“These exorbitant costs have made it extremely challenging to be able to continue to provide drug coverage to everyone who wants these drugs but does not have an FDA-approved medical condition or indication for these drugs,” the memo stated.

Insurers also point to inconsistent use of the medications. A report from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association’s data analytics arm showed that less than half of people who got GLP-1 prescriptions stayed on the medications beyond 12 weeks.

“Most people haven’t stuck with GLP-1s long enough to see a benefit,” said Dr. Razia Hashmi, the association’s vice president of clinical affairs. “This illustrates that there is much more to learn.”

Hashmi and insurance experts estimate that at the current list prices, it could eventually cost “over $1 trillion per year” to make GLP-1 medications available to all obese Americans.

“When families and employers make a significant investment, we want the result to improve health. Otherwise, we are contributing to the country’s health care affordability crisis,” Hashmi said. “Unfortunately, weight loss is not as simple as filling a prescription. Patients have the greatest chances of success when these medications are paired with lifestyle changes and collaboration with their health care provider.”

But Byers said limiting coverage for everyone hurts people like her, who are consistent in taking the medications and have made significant lifestyle changes. She argues that health insurers will still incur costs in the long run if people can’t use GLP-1 medications to prevent more serious health conditions that can develop from obesity.

“Whether it’s paying for a heart surgery for someone who has a clogged artery or a bariatric surgery for someone who is obese … it’s going to cost the insurance company something,” she said. “It’s up to them to decide how they want to pay for that.”

It’s a stressful situation, Byers said. The good news is that her IBX employer-sponsored coverage will continue to cover her medications through July, when the current plan ends. However, after that, she confirmed with the insurance company that coverage for Wegovy would mainly apply to certain conditions, but not for weight loss or obesity only.

“I think it sends a really terrible message to the public, which just kind of reinstates the stigma around obesity, saying that this is not a disease, this is a choice,” she said. “When we know through decades of research and [from] obesity specialists saying that this is a chronic disease and it does need to be treated.”

Patients scramble for new solutions

As a small business owner in Philadelphia, Rich Venezia buys his health insurance directly from IBX. He started taking Zepbound, a brand of the GLP-1 medication tirzepatide, in late September after hearing success stories among family and friends.

With some insurance coverage and a discount coupon from the pharmaceutical manufacturer, Venezia paid about $350 for a month’s supply of injections after meeting his deductible.

“Which was still a lot of money, but I thought, well, compared to the $1,100 or $1,300 [list] price, that was manageable,” he said.

But Venezia said he didn’t get a notice from IBX about changes to coverage for GLP-1 drugs until late December, which left him with little time to request additional refills before Jan. 1.

“I could have gotten myself a three-month supply and been able to at least have the ability to figure out what I was going to do,” he said, “but not having any time and having to scramble for no reason … that inability to make those decisions for myself when I am paying my monthly bills to this agency as their respected customer, it felt like an affront.”

In a statement, IBX said the company began notifying employer groups about the coverage change as early as August. They sent direct notices to individual plan members on Nov. 1 if they had been prescribed weight loss drugs before Sept. 4.

For people like Venezia, who started taking medication in late September or later, a second wave of notices was sent on Dec. 16.

After struggling with obesity and previous weight loss attempts over the years, Venezia said Zepbound has supported his efforts in keeping to a daily schedule of gym workouts and a high-nutritional meal plan.

The drug, which helps control appetite by slowing down digestion and making people feel fuller faster, also helped Venezia to identify and recognize what was triggering his past stress and binge eating.

“Once you have more knowledge about them and how your body is affected by stress eating and how much food you actually really need to feel satisfied, it certainly could make a long-term difference,” he said.

Without insurance coverage, Venezia said he is looking at paying about $650 a month. He said he can afford that in the short term, but it’s not something he can or wants to do indefinitely.

“I’m going to kind of reassess every time it’s due to order another box and see like, okay, do I want to spend this?” he said.

From a business perspective, Venezia said he doesn’t begrudge IBX for making this decision or the pharmaceutical companies from making money. What makes this situation upsetting, he said, is the sudden loss of his coverage, the limited timeline of communication, and the lack of affordable treatment options.

“I’m one very small fish in their very large pond of how they make money, right? But even still, when it comes to health care, it all feels really personal, right?” Venezia said. “It’s about how you feel and how you get through the world, and if you don’t have good health and good health care, it affects every other aspect of your life.”