Although humans’ visual perception of the world appears complete, our eyes contain a visual blind spot where the optic nerve connects to the retina. Scientists are still uncertain whether the brain fully compensates for the blind spot or if it causes perceptual distortions in spatial experience. A new study protocol, published in PLOS One, seeks to compare different theoretical predictions on how we perceive space from three leading theories of consciousness using carefully controlled experiments.

Predictions from three theories of consciousness

The new protocol focuses on three contrasting theories of consciousness: Integrated Information Theory (IIT), Predictive Processing Active Inference (AI), and Predictive Processing Neurorepresentationalism (NREP). Each of the theories have different predictions about the effects that the blind spot’s structural features have on the conscious perception of space, compared to non-blind spot regions.

IIT argues that the quality of spatial consciousness is determined by the composition of a cause-effect structure, and that the perception of space involving the blind spot is altered. On the other hand, AI and NREP argue that perception relies on internal models that reduce prediction errors and that these models adapt to accommodate for the structural deviations resulting from the blind spot. Essentially, this means that perceptual distortions should either appear small or nonexistent in both theories. However, AI and NREP differ in some ways.

“Specifically, NREP posits that lesions of portions of the visual field can have an effect on spatial estimates, but will be largely compensated for by the sensory evidence available from intact portions of the visual field.

“According to AI, the quality of spatial experience is determined by the cause-effect structure under a generative model apt for active vision. This model of projective geometry is not the geometry of anatomical projections. Thus, AI proposes that perceptual judgments should not be altered when involving the blind spot, other than possible changes in perceptual uncertainty, due to differences in sensory sampling,” the protocol authors explain.

Protocol tasks

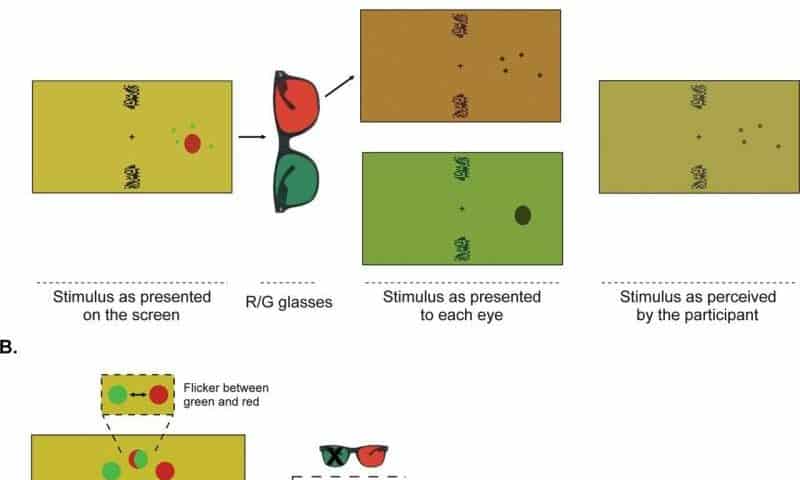

To test out the three theories, the researchers put together a series of three psychophysical tasks, which include distance estimation, area size matching, and motion curvature judgment, all near or away from the blind spot. The tasks use colored glasses for dichoptic presentation, which allows for stimuli to be shown to one eye at a time. The study also utilizes eye tracking to ensure accurate fixation and to prevent unintentional stimulation of the blind spot.

“We will explore the different theoretical accounts using three tasks quantifying different types of spatial perception in relation to the blind spot in healthy humans. In the distance task, participants will judge the distance of pairs of dots that either span or do not span the blind spot. In the area size task, participants will judge the apparent size of circles that either surround or do not surround the blind spot. In the motion task, participants will judge the apparent curvature of motion paths that either neighbor or do not neighbor the blind spot,” the team writes.

The team notes that effects from these tests might be small, so a larger sample size of around 32 participants per experiment would be needed. The collected data will then be analyzed using both linear mixed-effects models and Bayesian model comparison to determine how much evidence each theory accrues for its predictions.

Simulated results and potential issues

The research team also conducted analysis with simulated data of IIT, NREP and AI predictions for their distance estimation task, area size task and motion curvature task. The simulated data showed that IIT predicts spatial warping near the blind spot, while AI and NREP predict little or no distortion, with possible small decreases in precision.

As with most studies, there are potential limitations in interpreting the data when the actual experiments take place. For example, the theories in question predict the direction but not the magnitude of effects, making interpretation challenging.

The team also notes that unexpected results, such as an object appearing larger when it is predicted to appear smaller, may not be easily explained by any theory. Still, studies using the protocol have the potential to address some fundamental questions about how we perceive a seamless world with gaps in sensory input and may even advance the understanding of consciousness.