The office space firm is the capital’s largest private tenant but its very public and rapid retrenchment is making waves

At the UK headquarters of office space company WeWork, the skateboard half-pipe is empty, the arcade machines aren’t in use and the DJ turntables are motionless.

It could be because it’s 11am on a grey weekday in London, or it could be because this fast-growing company has suddenly found itself in crisis mode.

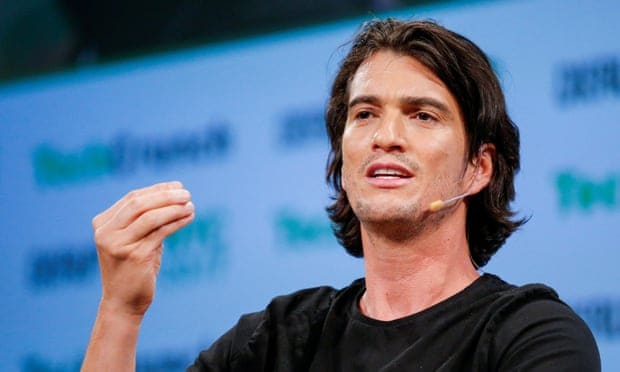

Having ejected controversial founder Adam Neumann from the chief executive’s seat, on Monday directors pulled the plug on a stock market listing.

A chastening retrenchment looms that could mean 5,000 job cuts – a third of the company’s global workforce. The company’s $60m (£49m) Gulfstream private jet is up for sale.

Less than two months ago, WeWork was seeking a price tag of $47bn from its now abandoned float. Bankers at Goldman Sachs reckoned it might have been worth much more, maybe $65bn. Now the firm, which has lost $3bn in the last two years, is reckoned to be worth $10bn. Tops.

There is even mounting concern that it could run out of cash altogether in 2020 unless Softbank – the Japanese tech investment giant that is WeWork’s largest shareholder with 29% – dips into its pocket again.

If WeWork were to fail, the tremors would be felt throughout the property industry, particularly in the UK.

Why? Because WeWork has quietly become the largest private tenant in London, as well as extending its reach beyond the capital to Birmingham, Manchester, Edinburgh and Cambridge, with 60 offices nationwide. Only the UK government has more office space in the capital.

In the past five years, it has signed lease agreements for 344,000 sq metres (3.7m sq ft) of office space – more than seven times the floorspace in the Gherkin tower in the City financial district.

It has even considered entering the residential market, as it has in the US, where it offers serviced apartments with communal yoga studios and espresso bars through its WeLive brand.

“They’ve expanded at an exponential rate and that was probably too fast,” said Mat Oakley, head of the UK and European commercial property research team at estate agent Savills.

He said: “Their occupancy rates are high and there’s definite demand for this but they have a lot of high fixed costs, regardless of whether [each building] is full or empty, or the yield per desk is going up or down.”

According to accounts filed at Companies House, UK landlords are expecting rent payments from WeWork that could top £5bn over the course of its lease agreements. The 2017 accounts show that subsidiaries of the UK parent company, WeWork International Ltd, have signed non-cancellable operating leases worth more than £3.2bn.

WeWork has formed at least 50 new companies since then, indicating rent commitments are likely to have risen substantially.

Each of these firms was created solely to house separate premises where office space could be hired out to new customers. If WeWork does decide it needs to shrink to survive, it could simply place some of those companies into administration, leaving landlords high and dry.

“The challenge will be if WeWork faces headwinds and takes the same route as retailers by folding those individual companies,” said one property industry veteran. “With so many WeWorks in close proximity to each other, it could easily consolidate tenants in one building, leaving a landlord with an empty space.”

This model, coupled with WeWork’s demands for lucrative concessions from landlords, has deterred some property owners from doing business with them.

Simon Wainwright, chief executive of JPW Real Estate, acted for the landlord of a large office building in the City in negotiations with WeWork this summer. His client opted for another tenant.

“They [WeWork] wanted 15-months’ rent free on an eight-year lease, but they also wanted us to cough up £100 a sq ft in a cash contribution; this would pay for their fit out, desks and generous introductory fees for the brokers they use,” he said.

The eventual rental offer was good, but Wainwright said there was no UK company guarantee if things went wrong.

“The problems will come further down the line when the rent-free [agreements] expire,” he said.

The back-loaded nature of WeWork’s rental agreements is one reason why the company is, in the short-term at least, able to offer customers so many freebies.

At its 16-storey London HQ in Waterloo, WeWork offers tenants – as well as its own employees – plenty of inducements on top of the skateboard ramp and DJ decks. Baristas brew free coffee all day long, while there are free classes with names such as “Wellness: Boomcycle” and “Yoga: The Flow”.

Far from expecting any job cuts, staff there were this week in good spirits, despite the meltdown of the IPO and the demotion of the group’s founder. One salesperson said there was no private office space left in the building.

This makes sense, despite WeWork’s public travail, according to Oakley.

“You have to separate the debate about whether the value of the company is right to whether the business model is right,” he said. “It’s a bit like some retailers that expand too fast but don’t stabilise income in existing stores. Their cash burn has more to do with expansion than whether existing centres are profitable.”

If the worst were to happen and WeWork were to fail, Oakley believes the London commercial property market wouldn’t suffer too much, as office space is undersupplied and in demand. Instead, he said, it could be the reputation of the serviced office industry that suffers.

“It would be very bad for the perception of this sector,” Oakley said. “The biggest shock would be to their ability to raise capital via debt or equity. A failure of this scale would draw into question the whole business model, rather unfairly. Aggressive expansion is not a new mistake.”