Neutrophils are the mercenaries of the immune system, but sometimes they’re messy fighters. The antimicrobial molecules they use as weapons don’t just knock out pathogens—in some cases, they damage healthy cells, too. When chronic or excessive, this activity is thought to be one of the mechanisms behind inflammatory conditions like sepsis, arthritis, atherosclerosis and some cancers, just to name a few.

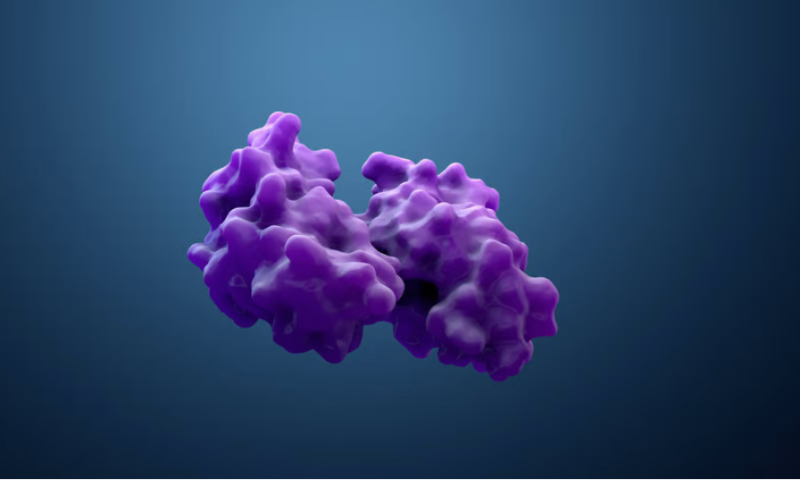

Now, a research team led by scientists from the Scripps Research Institute has identified a protein complex inside neutrophils that appears to regulate exocytosis, the process through which the cells release inflammatory molecules. They’re studying the compound—the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein and scar homolog, or WASH, protein complex—with the hope of identifying potential drug targets for inflammation, according to a paper published Sept. 21 in Nature Communications.

The WASH complex had previously been proposed to be involved in exocytosis, but the molecular mechanisms behind its activity were unclear. In their study, the Scripps team set out to better characterize its role.

A series of experiments in mouse cells showed that the protein complex serves as a gatekeeper of neutrophil exocytosis. In response to infection, it facilitates neutrophils’ initial release of relatively mild antimicrobial compounds while simultaneously restraining the release of azurophilic compounds, a set of molecules with far more potent effects against pathogens and host cells alike that are released when an infection is severe.

Further experiments in live mice shed light on how WASH dysregulation could result in inflammation spiraling out of control. When the researchers knocked out the gene for the protein complex in a group of mice, they found that they had high levels of azurophilic molecules in their blood and lower levels of the milder antimicrobial compounds. Inducing a sepsislike inflammatory condition in this population led to three times as many deaths than in the control group.

“WASH seems to be an important molecular switch that controls neutrophils’ responses to infection and inflammation by regulating the release of these two kinds of antimicrobial [molecules],” Sergio Catz, Ph.D., co-corresponding author, said in a press release. “When WASH is dysfunctional, the result is likely to be excessive and chronic inflammation.”

Next, the team led by the Scripps scientists is looking more closely at the WASH complex and other related compounds to find ways to inhibit the azurophilic molecules in inflammatory diseases without impairing neutrophils’ ability to fight invading pathogens.

The WASH complex adds to a growing list of potential avenues for targeting chronic or severe inflammation. In August, a team of researchers with ties to the University of Southwestern Medical Center identified an enzyme that appears to trigger the inflammatory cascade that leads to sepsis and found that in mice, an experimental cancer drug could inhibit it.