War movies, farm aid and the Long March: US, China appear to brace for prolonged trade conflict.

WASHINGTON — With negotiations on hold and tariffs piling up, the United States and China appear to be bracing for a prolonged standoff over trade.

Beijing is airing Korean War movies (antagonist: America) to arouse patriotic feelings in the Chinese public and offering tax cuts to software and chip companies as U.S. export controls threaten Chinese tech companies.

In Washington, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin is talking to Walmart and other companies about finding ways to ease the pain if President Donald Trump goes ahead with plans to extend import taxes to the $300 billion in Chinese products that haven’t already been hit with tariffs.

And the Trump administration is working on an aid package for American farmers hurt by China’s retaliatory tariffs on soybeans and other U.S. agricultural products — on top of last year’s $11 billion farm bailout.

Mnuchin and U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer wrapped up an 11th round of talks with the Chinese earlier this month without reaching an agreement to resolve a dispute over Beijing’s aggressive efforts to challenge American technological dominance. The U.S. charges that China is stealing technology, unfairly subsidizing its own companies and forcing U.S. companies to hand over trade secrets if they want access to the Chinese market.

“It’s really hard to identify whether this the beginning of a prolonged conflict or just negotiating tactics,” said David Dollar, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a former official at the World Bank and U.S. Treasury. “I increasingly think that this is going to turn into a long-term trade conflict. We have to entertain the possibility that there is no deal.”

Dollar points to the airing of Korean War movies and comments by President Xi Jinping suggesting that the Chinese people need to steel themselves for another “Long March” — a reference to the legendary and arduous trek Mao Zedong’s Communists made to escape pursuers from China’s ruling Nationalist government in 1934-1935.

The world’s two biggest economies are already locked in the costliest trade combat since the 1930s.

The United States has imposed 25% tariffs on $250 billion in Chinese imports and is planning to target another $300 billion — a move that would cover everything China ships to the United States.

China has targeted $110 billion in U.S. products in retaliation.

China is also looking at other ways to pressure the United States.

President Xi made it a point to visit a Chinese factory this week that processes rare earths — minerals used in things like mobile phones and electric cars. The unspoken message: The United States needs China to supply the exotic minerals.

China also turned up the heat on Boeing Co.: On Wednesday, two of China’s three major state-owned airlines — Air China Ltd. and China Southern Airlines Ltd. — demanded compensation for the grounding of the plane maker’s 737 Max jetliners after fatal crashes in Ethiopia and Indonesia. The third state-owned carrier — China Eastern Airlines Ltd. — made a similar request last month.

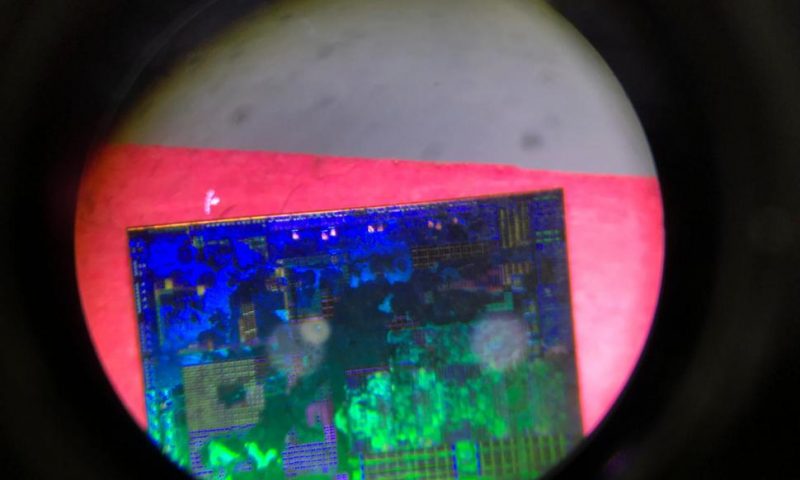

Meantime, the Chinese government took steps to protect tech companies from becoming collateral damage in the U.S.-China conflict.

Under the new measure, most software and integrated circuit companies can skip paying income taxes for two years and will see their tax bills cut by half for three years after that, the Finance Ministry said.

Most smartphones, tablet computers and other electronics are assembled in China. But Chinese manufacturers typically use U.S., Japanese or Taiwanese microchips and other components.

The United States has squeezed Chinese companies by threatening to shut off supplies of those key components. The Trump administration issued an order last week that will curb or end Chinese telecom giant Huawei Technologies Ltd.’s access to American chips and to Google, which provides the Android operating system and services for Huawei smartphones.

A similar export ban almost put the Chinese telecom firm ZTE Corp. out of business last year. The U.S. charged that the company had violated sanctions by selling equipment to Iran and North Korea. Eventually, ZTE escaped the export ban by agreeing to pay a $1 billion fine and to replace its management team.

In Washington, members of the House Financial Services Committee pressed Mnuchin Wednesday on the costs of the trade war with China. Mnuchin said he’d spoken to Walmart and other firms about how to limit the effect of higher tariffs on American consumers. “I don’t expect there will be significant costs on American families,” he said.

But many American businesses are not so sanguine.

Nearly 200 footwear retailers and brands including Adidas and Shoe Carnival wrote a letter to Trump on Monday, calling on him not to slap tariffs on footwear imported from China.

The group, the Footwear Distributors and Retailers of America, estimates that Trump’s proposed actions will add $7 billion in additional costs for customers every year.

Can the United States and China break the impasse?

No talks have been scheduled, and many analysts suspect a breakthrough will require an intervention at the top before the Group of 20 major economies meets next month in Osaka, Japan.

“For a deal, there needs to be a Trump-Xi call, which would enable a useful Lighthizer visit to Beijing,” said Derek Scissors, a China specialist at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. “Then the two leaders could meet in Osaka and compromise on at least one major issue: reinvigorating the talks.”