Kaileigh Baia still likes to play trivia-style games, though her memory recall is slower than it used to be before COVID-19.

She still gets to the gym. Last year she ran a 5K. However, it is important to pace herself now due to asthma-like breathing difficulties and being susceptible to more significant fatigue after activities.

It’s been more than four years since the 27-year-old Grand Rapids woman had her first bout with COVID-19. The illness caused lung inflammation, joint pain, damaged her vocal cords, left some of her favorite foods tasting and smelling rotten, and forced her to spend two weeks sleeping upright with breathing difficulties.

Baia is among the millions of Americans who have been diagnosed with long COVID, a complex, multisystem disorder associated with COVID-19 symptoms lasting longer than 90 days.

The most common symptoms of long COVID are fatigue; loss of sense of smell or taste; memory loss, brain fog, or disorientation; shortness of breath; general weakness; muscle weakness; joint pain; and hair loss.

Baia, a hospital referral coordinator, visited specialists and tried various therapies, attempting to regain the life she had before October 2020. As of March — 53 months after getting infected with coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) — she feels 85% to 90% recovered.

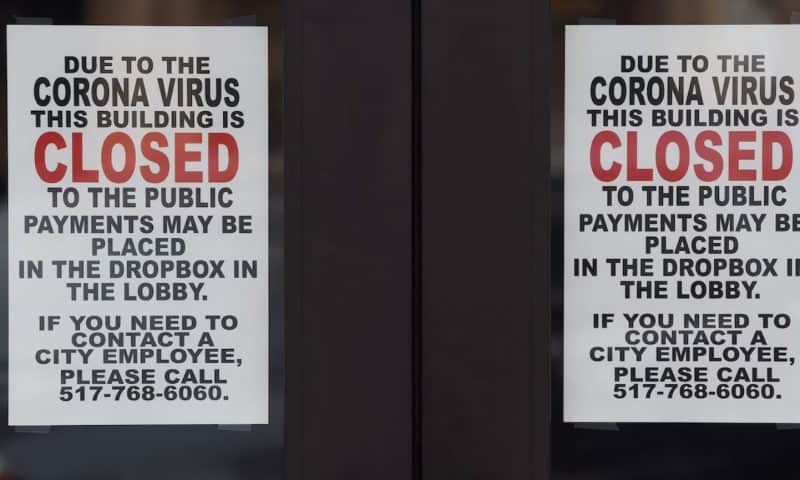

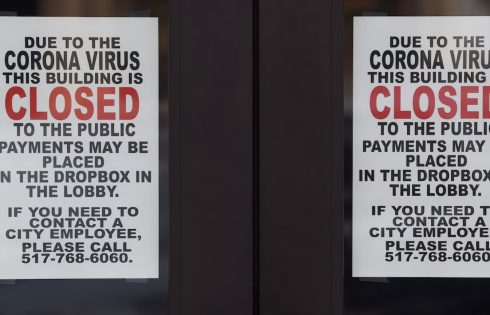

It’s been five years since the novel coronavirus rocked the world, killing millions of people, hospitalizing countless others, causing an economic crisis, and changing peoples’ day-to-day lives for the better part of three years.

Monday, March 10, marks the five-year anniversary of Michigan’s first reported cases of COVID-19. The death toll over five years is more than 39,760, according to state health records.

An estimated 20% of adults infected with COVID in 2020-2022 reported symptoms lasting 90 days or more, said Nancy Fleischer, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Michigan. National data estimated about 5% to 7% of all adults were experiencing long COVID in 2024.

Coronavirus isn’t the first virus to cause long-lasting effects. Other viruses like Epstein-Barr and West Nile have been associated with the chronic fatigue lasting weeks or months after infection.

“The reason long COVID became so prevalent is SARS-CoV-2 was so novel, there wasn’t a lot of immunity, and a lot of people experienced it at once,” Fleischer said. “Usually, people are infected with viruses at different times and with different levels of immunity.”

There’s been significant research on post-COVID conditions, ranging from their prevalence in various communities and which populations are most affected, to the physiological mechanisms causing the long-term effects.

Yet, many questions remain unanswered.

Years of not knowing what’s wrong or how to fix it has been challenging for those like Jennifer Gansler, 56, who felt left in the dark by medical experts who ran numerous tests but found little of significance to explain what ailed her.

“This whole idea of not getting better wasn’t on anybody’s radar,” said Gansler, an academic advisor at Michigan State University. “I struggled to find support in the medical community, and I had to do a lot of my own research.

“It’s been a lot of false starts, a lot of trial and error.”

Blazing your own trail

Gansler was among Michigan’s first confirmed cases of COVID-19. Following a trip to Spain, she got sick March 11, 2020, the same day the World Health Organization declared coronavirus a pandemic.

A self-described “super active, outdoors-y person,” she was an otherwise healthy mother who liked to run and hike, having tackled both the Porcupine Mountains and Chicago Marathon in 2019.

Her case of COVID didn’t require hospitalization, though she did visit an emergency room twice for breathing problems. She recovered at home in isolation, slowly waiting to get better.

After five months, she estimated she was 30% recovered. Crushing fatigue made it hard to get out of bed. She had chest tightness, a persistent cough, joint and muscle pain, and hair loss.

Simple tasks like taking a shower or talking on the phone left her winded. The prospects of running again seemed impossible.

Gansler worked with a chronic fatigue doctor. She tried supplements and medications. Everything she did made her crash, sending her back to bed.

For both Gansler and Baia, looking to others dealing with similar long-term symptoms made them feel less alone and offered glimpses hope for improvement.

Evolution of care

During much of the COVID pandemic, assessment of long COVID followed the traditional medical model of care, said Dr. Katharine Seagly, co-director of the Post-COVID Conditions Clinic at the University of Michigan.

Physicians would order blood tests, MRIs, CT scans and other screenings, attempting to find the exact mechanisms causing continued symptoms in patients. It was an expensive process with little value for patients like Gansler, who often felt they weren’t being heard or believed by doctors as test results came back normal.

“All these experts were seeing patients and running tests and finding a lot of nonsignificant results, which wasn’t a particularly helpful approach,” Dr. Seagly said.

“The idea of ‘I need a doctor to fix me,’ we know that’s not a helpful way of thinking about chronic conditions. Being able to have that sense of autonomy and self-management for chronic medical conditions is key for patient wellbeing.”

Most long COVID clinics that focused on the traditional medical model closed their doors.

Where U-M’s Post-COVID Conditions Clinic differed is it pivoted to an approach that focused more on function, behavioral medicine and rehabilitation. That included things like rehab, exercise, behavioral and mental health interventions.

The model centers around a six-session post-COVID recovery group led by neuropsychological and rehab psychology providers who equip patients with the education, skills and interventions to address their current symptoms and optimize their quality of life.

Seagly said they no longer use the term “long COVID” because it implies someone still has the virus. They prefer “post-COVID conditions” because it indicates multiple conditions affecting each patient differently.

As of December, the clinic had seen more than 1,000 patients. Referrals aren’t as high as they were previously, but they’ve remained steady over the last year.