Scientists at Walter and Elizabeth Hall Institute (WEHI) have made what they describe as a huge leap forward in the fight against Parkinson’s disease, solving a decades-long mystery by determining the first structure of the human protein PINK1 bound to mitochondria. First discovered more than 20 years ago, PINK1 is a protein directly linked to Parkinson’s disease, but until now, no one has seen what human PINK1 looks like, or how PINK1 attaches to the surface of damaged mitochondria to be switched on.

David Komander, PhD, head of WEHI’s Ubiquitin Signaling Division, said years of work by his team have now unlocked that mystery. “This is a significant milestone for research into Parkinson’s. It is incredible to finally see PINK1 and understand how it binds to mitochondria,” said Komander, who is also a laboratory head at the WEHI Parkinson’s Disease Research Centre. “Our structure reveals many new ways to change PINK1, essentially switching it on, which will be life-changing for people with Parkinson’s.” Komander is corresponding author of the team’s published paper in Science, titled “Structure of human PINK1 at a mitochondrial TOM-VDAC array.”

Parkinson’s disease is insidious, often taking years, sometimes decades to diagnose. Commonly associated with tremors, there are close to 40 symptoms, including cognitive impairment, speech issues, body temperature regulation, and vision problems. In Australia, more than 200,000 people live with Parkinson’s disease, and between 10% and 20% have a young onset form of the disease (early onset Parkinson’s disease; EOPD), meaning they are diagnosed under the age of fifty years.

One of the hallmarks of Parkinson’s is the death of brain cells. Around 50 million cells die and are replaced in the human body every minute. But unlike other cells in the body, when brain cells die, the rate at which they are replaced is extremely low.

Mitochondria produce energy at a cellular level in all living things, and cells that require a lot of energy can contain hundreds or thousands of mitochondria. The PARK6 gene encodes the PINK1 protein, which supports cell survival by detecting damaged mitochondria and tagging them for removal. “PINK1 is a ubiquitin and Parkin kinase and functions as an early sensor and transducer of mitochondrial damage signaling,” the authors explained.

When mitochondria are damaged, they stop making energy and release toxins into the cell. In a healthy person, when mitochondria are damaged, PINK1 gathers on mitochondrial membranes and signals through a small protein called ubiquitin, that the broken mitochondria need to be removed. In a healthy person, the damaged cells are disposed of in a process called mitophagy. The PINK1 ubiquitin signal is unique to damaged mitochondria, and when PINK1 is mutated in patients, broken mitochondria accumulate in cells.

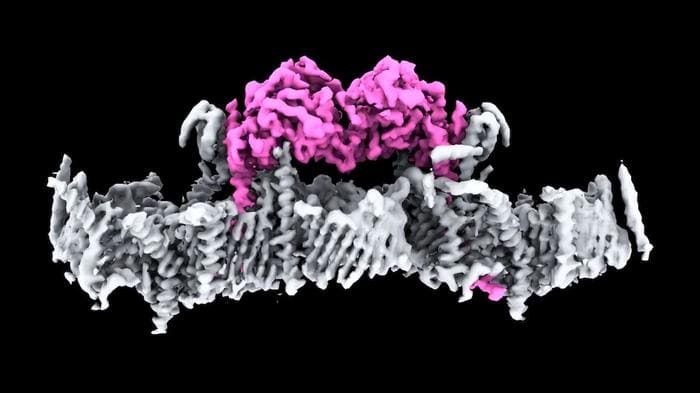

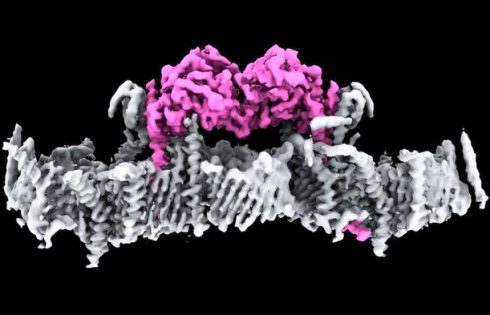

Study lead author and WEHI senior researcher Sylvie Callegari, PhD, said PINK1 works in four distinct steps, with the first two steps not having been seen before. First, PINK1 senses mitochondrial damage. Then it attaches to damaged mitochondria. Once attached it tags ubiquitin, which then links to a protein called Parkin so that the damaged mitochondria can be recycled. In their paper, the authors explained further, “In healthy mitochondria, PINK1 is translocated across the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) via the translocase of the outer membrane (TOM) complex, inserted into the mitochondrial inner membrane (MIM) via the translocase of the inner membrane (TIM)23 complex, cleaved by the MIM protease PARL, retro-translocated and degraded by the proteasome.”

In a person with Parkinson’s and a PINK1 mutation, the mitophagy process no longer functions correctly and toxins accumulate in the cell, eventually killing it. “Mutations in the ubiquitin kinase PINK1 cause early onset Parkinson’s disease,” the authors noted. “A structure of full-length PINK1 at mitochondria is crucial to develop and understand PINK1 activators and treat Parkinson’s disease.”

However, scientists to date have been unable to visualize the protein or understand how it attaches to mitochondria and is switched on. The authors noted that while multiple structures of isolated kinase domains of PINK1 from insects have given scientists molecular details about PINK1 activation, “… human PINK1 has resisted structural characterization, and the PINK1 N terminus which comprises many patient mutations has remained unresolved …”

Commenting on their newly reported work, Callegari said, “This is the first time we’ve seen human PINK1 docked to the surface of damaged mitochondria and it has uncovered a remarkable array of proteins that act as the docking site. We also saw, for the first time, how mutations present in people with Parkinson’s disease affect human PINK1.”

The idea of using PINK1 as a target for potential drug therapies has long been touted but not yet achieved because the structure of PINK1 and how it attaches to damaged mitochondria were unknown. The research team hopes to use the knowledge to find a drug to slow or stop Parkinson’s in people with a PINK1 mutation. “Our structure also provides multiple unexplored avenues to stabilize PINK1 on mitochondria, to develop much-needed treatment options for Parkinson’s disease patients,” the scientists wrote.