Panic disorder (PD) is a mental health disorder characterized by recurring panic attacks, episodes of intense fear and anxiety accompanied by physical sensations and physiological responses such as a racing heart, shortness of breath, dizziness, blurred vision and other symptoms. Estimates suggest that approximately 2–3% of people worldwide experience PD at some point during their lives.

Better understanding the neural underpinnings and features of PD could have important implications for its future treatment. So far, however, most neuroscientific studies have examined the brains of relatively small groups of individuals diagnosed with the disorder, which poses questions about whether the patterns they observed are representative of PD at large.

Researchers at the Amsterdam University Medical Center, Leiden University and many other institutes worldwide recently carried out a new study shedding new light on the neuroanatomical signatures of PD, via the analysis of a large pool of brain scans collected from people diagnosed with the disorder and others with no known psychiatric diagnoses. Their paper, published in Molecular Psychiatry, identifies marked differences in the brains of individuals with PD, such as a slightly thinner cortex and frontal, temporal and parietal brain regions that are smaller than those of people with no known mental health disorders.

“Neuroanatomical examinations of PD typically involve small study samples, rendering findings that are inconsistent and difficult to replicate,” Laura K. M. Han and Moji Aghajani, first and senior authors of the paper, respectively, told Medical Xpress.

“This motivated the ENIGMA Anxiety Working Group to collate data worldwide using standardized methods, to conduct a pooled mega-analysis. The main goal was to provide the most reliable test to date of whether PD is associated with robust neuroanatomical alterations, and whether these differences may vary by age or clinical features (e.g., age of onset, medication use, severity).”

Uncovering the brain signatures of panic disorder

As part of their study, Han, Aghajani and their colleagues analyzed brain scans collected by different research teams worldwide from a total of almost 5000 people between 10 and 66 years old, including 1,100 individuals with PD and 3,800 healthy control subjects. The brain scans were collected using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), an imaging technique that is commonly used by both scientists and doctors to study and diagnose various diseases.

“Using harmonized ENIGMA protocols and the FreeSurfer brain segmentation software, we measured cortical thickness, cortical surface area, and subcortical volumes,” explained Han and Aghajani. “Statistical mixed-effects models compared PD and healthy controls on these brain metrics, while accounting for individual variations in age, sex, and scanning site.”

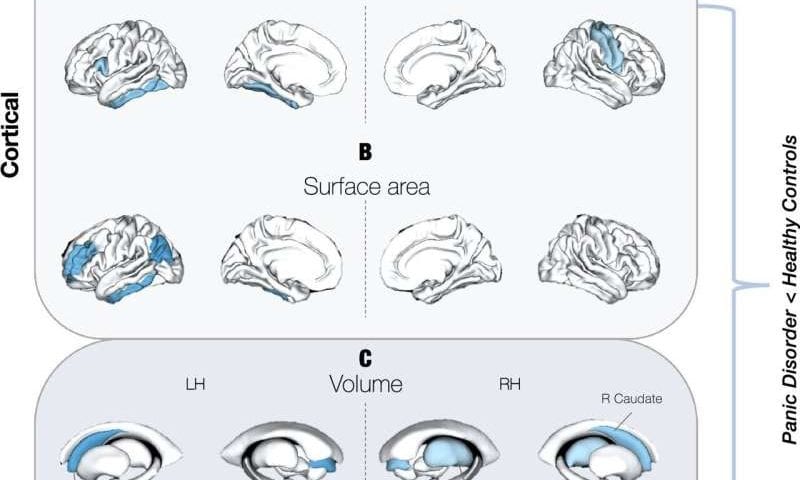

The team’s analyses allowed them to pin-point various marked differences between the brains of people with PD and others with no known psychiatric or mental health disorders. The researchers found that people with PD had a slightly thinner cortex and that some parts of their brain had a smaller surface area or a reduced volume.

“We identified subtle but consistent reductions in cortical thickness and surface area in frontal, temporal, and parietal regions, along with smaller subcortical volumes within the thalamus and caudate volumes, among individuals with PD,” said Han and Aghajani.

“Among other things, these regions govern how emotionally salient information is perceived, processed, modulated, and responded to. The analyses also showed that some differences are age-dependent and that early-onset PD (before age 21) is linked to larger lateral ventricles.”

Paving the way for the detailed mapping of psychiatric disorders

Overall, the findings of this recent study appear to confirm existing models of PD that suggest that the disorder is linked to disruptions in brain regions associated with the processing and regulation of emotions. In the future, they could inspire other researchers to conduct further research that closely examines some of the newly uncovered neuroanatomical signatures of PD, perhaps also looking at how they change at different stages of development or when patients are responding well to specific treatments and psychotherapeutic interventions.

The team’s mega-analysis also highlights the value of examining large amounts of data, showing that this can contribute to the detection of subtle neuroanatomical changes or differences that might be hard to uncover in smaller samples. A similar approach has also been used to study the neuroanatomy of other neuropsychiatric disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), bipolar disorder (BP), schizophrenia or substance use disorders (SUDs).

“Future studies could track individuals with PD longitudinally to clarify developmental and aging effects, integrate genetics and environmental risk factors, and combine structural imaging with functional and connectional brain examinations,” added Han and Aghajani. “The results also motivate transdiagnostic comparisons across anxiety disorders and efforts to link brain differences to prognosis, treatment response, or prevention strategies, rather than diagnosis alone.”