Researchers may have found a way to make the invisible visible when it comes to detecting small yet life-threatening complications after surgery.

Leaks of the acidic fluid from the digestive tract into the body’s surrounding tissues following a gastric or colorectal procedure can become a severe problem—especially so because the condition can be hidden from ultrasound exams as well as CT and MRI scans.

Known as anastomotic leaks, they can bring severe pain, high fevers and a rigid abdomen, as well as septic infections, and may require intensive care. They occur after as many as 5% of surgeries such as bowel resections to treat tumors or procedures that join together different sections to divert flow through the small intestine.

To provide some kind of an early warning system, researchers at Northwestern University and Washington University in St. Louis have developed a relatively simple approach: a small, bioabsorbable sticker that can twist into different shapes based on changing pH levels.

When attached to the outside of an organ, it can be seen and monitored with ultrasound. After the patient has fully recovered, the hydrogel sticker dissolves and is taken away by the body.

“These leaks can arise from subtle perforations in the tissue, often as imperceptible gaps between two sides of a surgical incision,” said John Rogers, Ph.D., director of Northwestern’s Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics.

“We developed an engineering approach and a set of advanced materials to address this unmet need in patient monitoring. The technology has the potential to eliminate risks, reduce costs and expand accessibility to rapid, non-invasive assessments for improved patient outcomes,” added Rogers, who led the device’s development with postdoctoral fellow Jiaqi Liu.

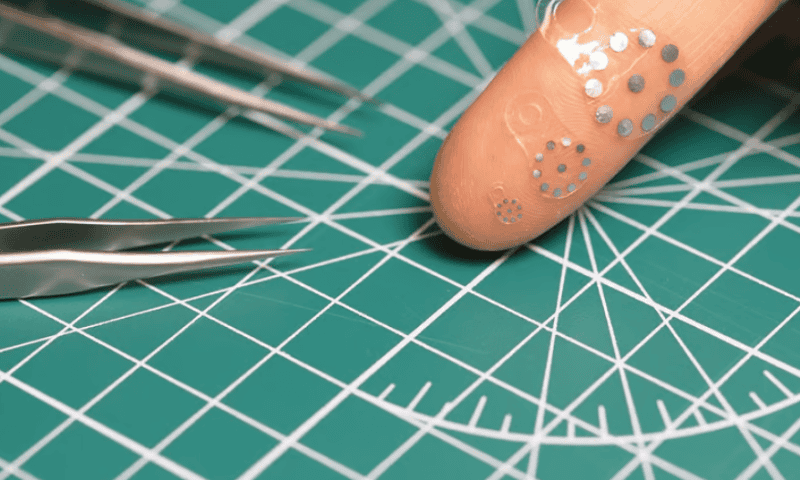

The thin sticker is embedded with millimeter-wide metal disks that allow it to stand out clearly from the fluid around it within an ultrasound image. When the hydrogel material comes into contact with acidic fluids such as stomach acid, it begins to swell and spread out the disks. In a more alkaline environment, such as in bile and fluids from the pancreas, it starts to contract.

“Right now, there is no good way whatsoever to detect these kinds of leaks,” said gastrointestinal surgeon Chet Hammill, M.D., who led the clinical evaluation and animal model studies at Washington University with Matthew MacEwan, Ph.D., an assistant professor of neurosurgery. “The majority of operations in the abdomen—when you have to remove something and sew it back together—carry a risk of leaking. We can’t fully prevent those complications, but maybe we can catch them earlier to minimize harm.”

“Even if we could detect a leak 24- or 48-hours earlier, we could catch complications before the patient becomes really sick,” said Hammill—who estimates that spotting it late could mean a gastrointestinal patient has a 30% chance of spending up to six months in the hospital as well as a 20% chance of dying. Meanwhile, 40% to 60% of patients suffer complications after pancreas-related surgeries, he said.

“Patients might have some vague symptoms associated with the leak,” said Hammill. “But they have just gone through big surgery, so it’s hard to know if the symptoms are abnormal. If we can catch it early, then we can drain the fluid. If we catch it later, the patient can get sepsis and end up in the ICU. For patients with pancreatic cancer, they might only have six months to live as it is. Now, they are spending half that time in the hospital.”

“The fluid might show up in a CT image, but there’s always fluid collections after surgery. We don’t know if it’s actually a leak or normal abdominal fluid,” he said. “The information that we get from the new patch is much, much more valuable. If we can see that the pH is altered, then we know that something isn’t right.”

The developers envision a sticker that could simply be left behind at the end of a surgery, or a flexible version that can be rolled up in a syringe and implanted into the body—while future versions may be tuned to react to internal bleeding or temperature changes. The researchers’ work was published in the journal Science.