Over a year into its recall of more than 5 million respiratory devices distributed around the world, Philips this week reported the results of its testing on the polyester-based polyurethane (PE-PUR) foam at the center of the Class I recall.

The foam—which is used to muffle sound in ventilators, CPAP and BiPAP machines and other breathing support devices—has been found to be at risk of breaking down over time, potentially sending foam particles, debris and untested chemicals into a user’s airstream.

In just the year between April 2021 and April 30 of this year, the FDA received more than 21,000 complaints related to the issue, the agency said in May. Those included reports of cancer, pneumonia, asthma, infection, headache, nodules and chest pain in patients using the Philips devices, as well as 124 patient deaths. However, the FDA noted at the time that not all of the complaints were necessarily caused by the polyurethane foam, citing “under-reporting of events, inaccuracies in reports, lack of verification that the device caused the reported event and lack of information about frequency of device use.”

Indeed, in its analysis of more than 60,800 recalled devices that were returned by users in the U.S. and Canada to be repaired or replaced, Philips said just 422 had been linked to a formal complaint of foam breakdown—and only 18 of those devices, or about 4%, actually showed signs of degradation in the material in visual assessments.

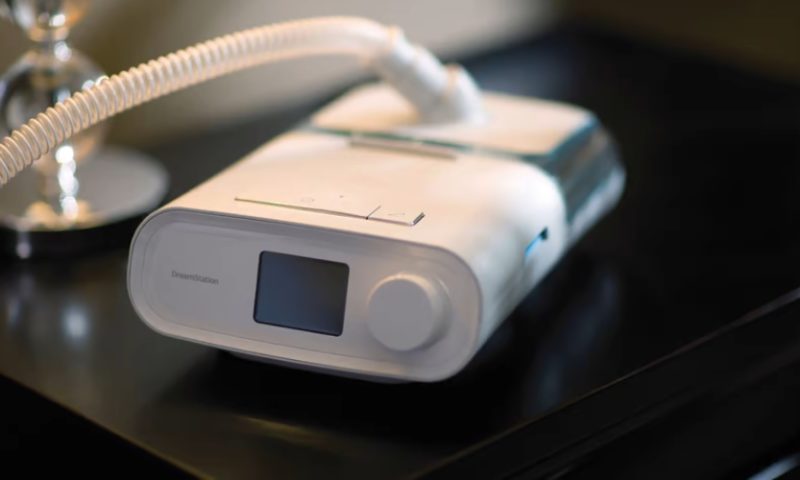

The analysis focused on first-generation DreamStation CPAP machines, which represent more than two-thirds of all devices included in the global recall.

The independent testing laboratories tapped by Philips did observe significant degradation in at least 941 of the sample of North American devices, regardless of whether they were accompanied by a formal complaint.

Even so, the company noted that as the foam degrades, it may not actually send particles and chemicals into the airflow.

“The foam becomes hygroscopic (i.e., absorbs moisture) and sticky with degradation. It also loses significant volume and increases density as the structure changes from a foam to viscous liquid material. As such, even when foam particulates are formed by degradation, they are likely to accumulate within the device and may not be directly emitted by the device,” Philips said in a statement—but added that testing is still ongoing to confirm that hypothesis.

Additionally, tests of the particles emitted from the degrading PE-PUR foam found that their emissions levels fell below standard limits for particulate matter and volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions, with Philips concluding, “Exposure to the level of VOCs identified to date for the first-generation DreamStation devices is not anticipated to result in long-term health consequences for patients.”

Philips also zeroed in on foam breakdown in devices that had been cleaned either with or without an ozone cleaner. These are devices that emit ozone gas and claim to sanitize medical devices of bacteria, germs and other pathogens—though the FDA hasn’t authorized any such cleaners for use with CPAP machines or their accompanying accessories, recommending instead that they be cleaned simply with soap and water.

Of the 36,341 machines in the sample whose users hadn’t used ozone cleaners, only 164—or about 0.5%—showed “significant visible foam degradation.” Meanwhile, just over 11,300 were linked to ozone cleaner use, and 7% of the devices in that group experienced significant degradation.

Philips framed those results as indicating that the use of ozone cleaning made it 14 times more likely that a device would have significant visible foam degradation. And in a statement about the testing, Philips CEO Frans van Houten said, “Results to date … indicate that ozone cleaning significantly exacerbates foam degradation.”

While the company seemed to place much of the blame for the recall on ozone cleaners in its report, the FDA has made a specific point of discounting that idea. In a letter (PDF) sent to Philips at the beginning of May, the regulator said, “although the use of ozone cleaners by device users may have exacerbated degradation of the PE-PUR foam, evidence indicates that the unreasonable risk associated with the products was not caused by the use of ozone cleaning agents, nor did the use of ozone to clean the products constitute a failure to exercise due care.”

Instead, both the FDA and Philips itself have previously concluded that the foam’s degradation can actually be primarily attributed to “long-term exposure to environmental conditions of high temperature combined with high humidity,” according to the letter.

Documents unsealed earlier this month in a class-action lawsuit against Philips confirmed that the devicemaker knew about those potential effects on the foam several years before beginning to formally investigate the issue in early 2021.

In a statement sent to Fierce Medtech regarding Philips’ latest report, the lead attorneys for the plaintiffs in the class-action case said, “Philips knew as far back as 2015 that the foam it used in the recalled devices would degrade, creating an unreasonable health hazard to patients, but waited until June 2021 to issue a recall.”

They continued, “Philips’ actions have forced millions of sleep apnea patients to choose between using an unsafe product or going without needed treatment. Rather than taking ownership of its mistakes, the company continues to deflect blame and attempt to cover up the full extent of the risks to users. We look forward to holding Philips fully accountable for its misconduct.”