The gastrointestinal tract is continuously exposed to foreign antigens in food and commensal microbes that have the potential to induce adaptive immune responses for food allergies.

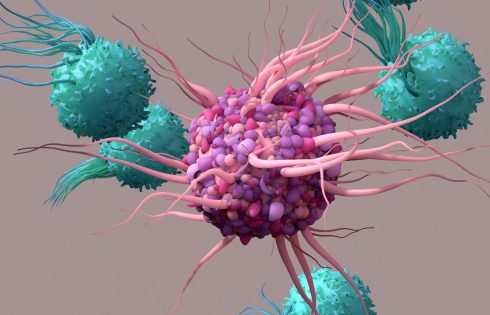

In a new study published by Nature titled, “Prdm16-dependent antigen-presenting cells induce tolerance to gut antigens,” researchers from New York University (NYU) Langone Health have revealed that a special group of cells in the intestines, termed tolerogenic dendritic cells (tDC), reduce the immune responses caused by exposure to food proteins to prevent allergies.

Upon genetic perturbation of tDC, the authors observed a compromised tolerance in mouse models of asthma and food allergy, as illustrated by a substantial increase in food antigen-specific T helper 2 (Th2) cells, which are involved in immune responses against extracellular parasites and allergies. Alternatively, food antigen presentation from tDC led to an anti-inflammatory T-cell response.

Specifically, tDC development and function required the proteins Retinoic Acid-Related Orphan Receptor-gamma-t (RORγt) and PR domain-containing 16 (Prdm16) to effectively protect tolerated proteins from the inrush of immune cells and proteins meant to destroy foreign cells.

“This discovery adds evidence to our earlier work showing that these cells also keep the peace with the vast microbiome, the mix of microbes that inhabits our body, and may be important for preventing autoimmune conditions like Crohn’s disease,” said Dan Littman, MD, PhD, corresponding author of the study and a professor in the department of cell biology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

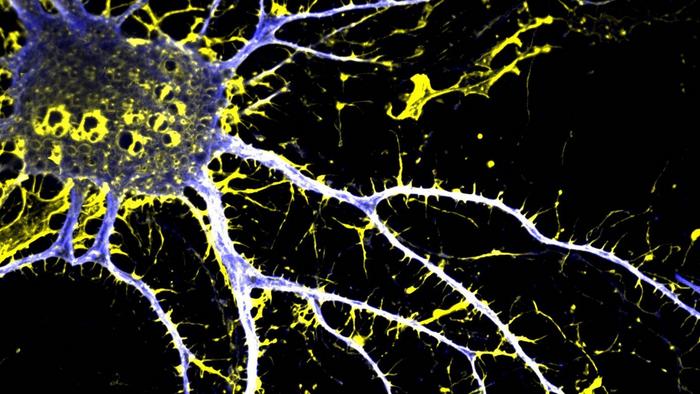

To illustrate that tDC were a distinct subset of cells, researchers used gene expression, chromatin, and surface marker analysis, to demonstrate that tDC were separate from innate lymphocytes, which play a crucial role in maintaining gut homeostasis and regulating immune responses. Additionally, tDC shares epigenetic profiles with classical dendritic cells, a type of antigen-presenting cell (APC) that initiates and regulates the immune response by programming T cells to launch an immune attack.

Additionally, single-cell analyses of freshly resected lymph nodes in the intestines from a human organ donor and specimens of human intestine and tonsil, revealed an extensive transcriptome shared with mice, highlighting an evolutionarily conserved role across species.

“If further experiments prove successful, our findings could lead to innovative ways to treat food allergies,” said Littman. “For example, if someone has a peanut allergy, perhaps we can use tolerogenic dendritic cells to help create more regulatory T cells to suppress an allergic response to peanut molecules.”

Moving forward, Littman said the researchers want to more deeply understand how and where tolerogenic dendritic cells develop in the body and what signals are needed to perform their function. Such insights could drive the development of therapeutic strategies for autoimmune and allergic diseases as well as organ transplant tolerance.