Recently, scientists have been able to explore gene circuitry in individual cells using methods that suppress particular genes and measure the impact on the expression of other genes. These methods, however, fail to capture spatial information such as the effects from, or on, neighboring cells, which can provide important clues to a cell or gene’s role in health and disease.

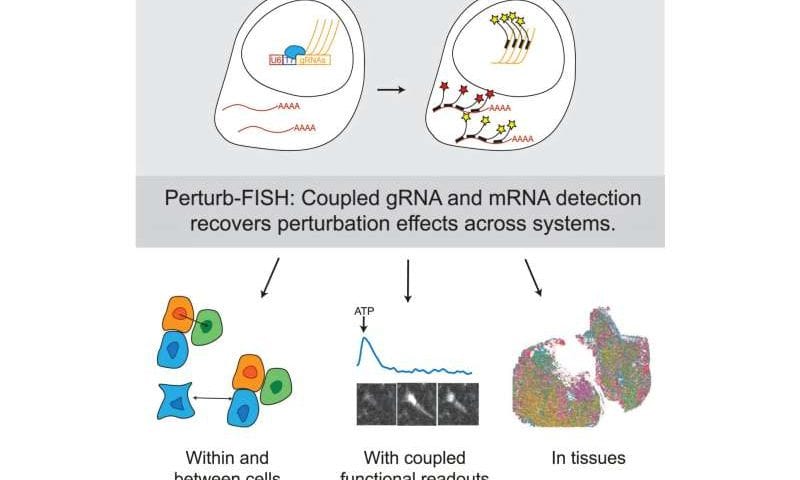

Now, a technology developed in the Spatial Technology Platform at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard builds on these methods with cutting-edge spatial advances. Their method, known as Perturb-FISH, combines imaging-based spatial transcriptomic measurements with large-scale detection of CRISPR guide RNAs.

The researchers demonstrated Perturb-seq’s ability to uncover new cellular and functional insights, including the effects of autism-related genes on cellular activity and the interactions between human tumor and immune cells in an animal model. Further refinements to Perturb-FISH could make it even more widely accessible and enable a range of new biological investigations. The technology and demonstrations of its utility are published in Cell.

“With Perturb-FISH, we’ve developed a powerful new way to examine the roles of genes and genetic circuits in tissue development, homeostasis, and dysfunction,” said co-senior author Sami Farhi, director of the Spatial Technology Platform at the Broad Institute.

“Our team is dedicated to devising spatial tools for the benefit of the scientific community, and we hope this new method is just the first of many more that we’ll build and share.” Farhi led the work along with co-senior author Brian Cleary, a former Broad Fellow and Merkin Institute Fellow who is now an assistant professor at Boston University.

Gone FISH-ing

Previously, researchers had combined single-cell RNA sequencing with CRISPR screening to examine gene networks within cells using tools such as Perturb-seq, but the cells’ spatial context wasn’t captured. Another method known as optical pooled screening measures the effects of gene-editing perturbations on cell fitness or other phenotypes, but doesn’t capture gene transcriptional states.

Scientists in the Spatial Technology Platform aimed to develop a comprehensive method that could measure at once which genes are altered in a cell, which genetic perturbation caused the changes, and the location of those affected cells in relation to other cells.

Key developments that made Perturb-FISH possible were computational methods developed by Cleary and a new way of amplifying the signal from single molecules (either CRISPR guide RNAs or gene transcripts) so they can be detected over background levels of fluorescence.

Traditional amplification methods don’t work with molecules as small as guide RNAs, so first author and former postdoctoral researcher Loϊc Binan devised an innovative strategy to generate many local copies of each guide RNA at its original site. By combining that with a fluorescence-based spatial transcriptomic method called MERFISH, Perturb-FISH can reveal both the identity of each perturbation and the cell’s transcriptome in their spatial context.