New research from scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) describes a process for converting skin cells directly into neurons that bypasses the induced pluripotent stem cell (IPSC) stage. Details are provided in a pair of papers that were published in Cell Systems. The first paper is titled “Proliferation history and transcription factor levels drive direct conversation to motor neurons.” The second paper is titled “Compact transcription factor cassettes generate functional, engraftable motor neurons by direct conversion.”

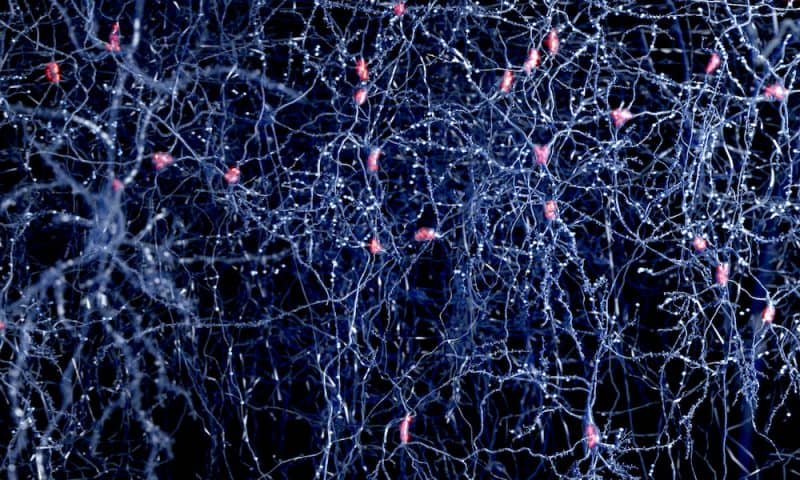

Working with mouse cells, the researchers developed an efficient conversion method for producing more than 10 neurons from a single skin cell. According to the study, the researchers successfully generated motor neurons and engrafted them into mouse brains, where they integrated with the host tissue. If they can replicate the process using human skin cells, this could be a way to generate large quantities of motor neurons for cell therapies to treat spinal cord injuries or other neurodegenerative diseases that impair mobility.

“We were able to get to yields where we could ask questions about whether these cells can be viable candidates for the cell replacement therapies, which we hope they could be. That’s where these types of reprogramming technologies can take us,” said Katie Galloway, PhD, senior author on both studies and a professor in biomedical engineering and chemical engineering at MIT.

The established way of reprogramming cells is to use four transcription factors that coax them to become IPSCs. These can then be differentiated into other cell types of interest. The process takes several weeks and many cells fail to fully transition to mature cell types, remaining stuck in intermediate states. To avoid this, Galloway and her colleagues came up with a way to directly convert somatic cells to neurons without the intermediate iPSC step.

In a previous study, the scientists demonstrated this type of direct conversion, but with very low yields—less than 1%. That approach used a combination of six transcription factors plus two other proteins that stimulate cell proliferation. Each of the eight genes that encode for these projects was delivered using a separate viral vector. And that made it difficult to ensure that each was expressed at the correct level in each cell.

Galloway and her team have now streamlined the process so that skin cells can be converted to motor neurons using just three transcription factors, plus the two genes. Using mouse cells, the researchers experimented with different combinations of the original six transcription factors. They dropped one factor at a time until they reached a combination of three—NGN2, ISL1, and LHX3—that successfully accomplished the conversion from skin cells to neurons.

Once they narrowed the number of relevant genes down to three, the researchers used a single modified virus to deliver all three, ensuring that each cell expresses each gene at the correct levels. Using a separate virus, the researchers also delivered genes that encoded for p53DD and a mutated version of HRAS. These genes drive the skin cells to divide many times before they start converting to neurons, allowing for a much higher yield of neurons.

That last step is important because “if you were to express the transcription factors at really high levels in non-proliferative cells, the reprogramming rates would be really low, but hyperproliferative cells are more receptive. It’s like they’ve been potentiated for conversion, and then they become much more receptive to the levels of the transcription factors,” Galloway explained.

The researchers have now developed a slightly different combination of transcription factors that allows them to perform this direct conversion in human cells but with a lower efficiency rate—between 10–30%. This process takes about five weeks, which is slightly faster than converting the cells to iPSCs first and then turning them into neurons.

Once they identified the optimal combination of genes to deliver, the researchers also worked on improving their delivery mechanism. After testing three different delivery viruses, they found that a retrovirus achieved the most efficient rate of conversion. Reducing the density of cells grown in the dish also helped to improve the overall yield of motor neurons.

As part of their study, the researchers tested whether the motor neurons generated by their process could be engrafted into mice brains. They delivered the cells to the striatum, a part of the brain involved in motor control and other functions. Two weeks later, many of the neurons had survived and seemed to be forming connections with other brain cells. The cells also showed measurable electrical activity and calcium signaling, which suggests that they may be able to communicate with other neurons.

The researchers now plan to explore the possibility of implanting these neurons into the spinal cord. They also hope to increase the efficiency of this process for human cell conversion.