An arms race is unfolding in our cells: Transposons, also known as jumping genes or mobile genetic elements as they can replicate and reinsert themselves in the genome, threaten the cell’s genome integrity by triggering DNA rearrangements and causing mutations. Host cells, in turn, protect their genome using intricate defense mechanisms that stop transposons from jumping.

Now, for the first time, a retrotransposon has been caught in action inside a cell: Refining cryo-Electron Tomography (cryo-ET) techniques, scientists imaged the retrotransposon copia in the egg chambers of the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster at sub-nanometer resolution. The paper is published in the journal Cell.

Among the international team of scientists achieving this detailed visualization are three scientists with Vienna BioCenter ties: Sven Klumpe, currently in the laboratory of Jürgen Plitzko at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried, will join IMBA and IMP to build a group as a Joint Fellow; Julius Brennecke, a Senior Group Leader at IMBA, the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences; and Kirsten Senti, staff scientist in the Brennecke group. Also involved in this collaboration is the group of Martin Beck at the Max Planck Institute of Biophysics in Frankfurt.

Cryo-Electron Tomography is an imaging technique used to visualize cellular landscapes in three dimensions at molecular resolution. In cryo-ET, a series of 2D images is captured from various angles of the sample, and then combined to form a detailed 3D reconstruction. Cryo-ET has given researchers unprecedented insights into the ultrastructure of cells.

So far, however, cryo-ET has mostly been used to image unicellular organisms, as cryo-ET samples must be rapidly frozen in a process known as “vitrification” to prevent ice crystal formation. Multicellular tissues, which require high-pressure freezing for vitrification, are typically too thick to be prepared for cryo-ET imaging using standard methods.

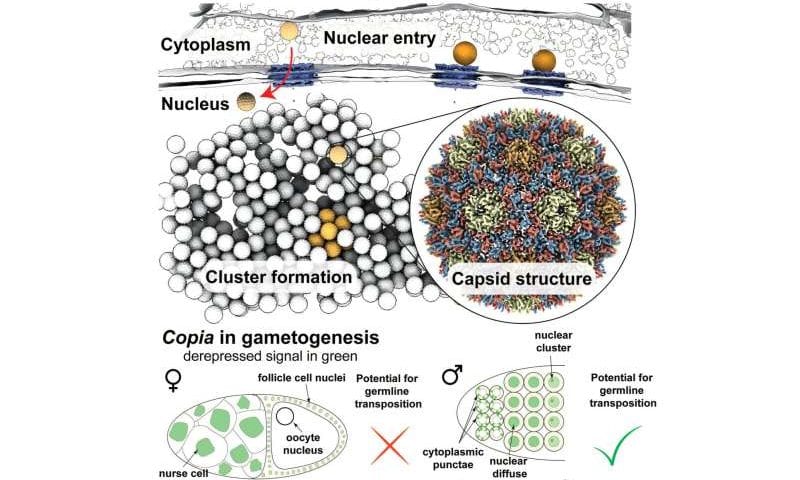

Capsid resembles retroviral capsids

In the new study, the researchers employed cryo-lift-out, a technique that allows researchers to prepare complex tissues for cryo-ET by combining focused ion beams and advanced micromanipulation techniques at cryogenic temperatures. Working with egg chambers of Drosophila melanogaster and cells isolated from them, the researchers resolved the structure of the retrotransposon copia’s capsid to 7.7 Å resolution—the first structure of a retrotransposon at sub-nanometer resolution in its native cellular environment.

Employing recent advances in AI-based structure prediction, the team generated an integrative model of capsid assembly using AlphaFold 2, allowing the researchers to subsequently design structure-guided experiments. Through this, they were able to show that the copia retrotransposon adopts a capsid fold similar to the mature capsid of HIV-1, confirming previous observations of transposable element structures from purified samples.

Insights into the retroviral lifecycle

Klumpe and colleagues also provided snapshots of copia’s replication cycle within intact egg chambers. Similar to retroviruses, retrotransposons are transcribed from the genome, the transcript is exported and translated in the cytoplasm, where virus-like particles form. Finally, their RNA genome is reverse transcribed. However, a major problem in retrotransposon research revolves around the question of how a retrotransposon gets back into the nucleus, where a new copy of the retrotransposon integrates into the host genome.

Looking at copia capsids inside the cell, the researchers discovered that viral particles in the cytoplasm are within reach of nuclear pores, which connect the cytoplasm and the nucleus. Similar to the evolutionarily related HIV-1, copia likely enters the nucleus as intact particles by traveling through nuclear pores.

Here, the nuclear pore complex appears to act like a molecular sieve: only viral particles of a certain size are observed in, and therefore enter, the nucleus. Furthermore, genetic manipulation, which disturbed the active transport through nuclear pores, led to the copia particles being retained in the cytoplasm.

Although many retrotransposons are found in the Drosophila genome, copia is by far the most frequently expressed one. Previous research has shown that copia predominantly targets the male germ line. In the new study, the researchers also explored how Drosophila’s transposon repression system, the PIWI-piRNA pathway, silences copia.

In the fruitfly testes, anti-sense piRNAs targeting copia turned out to be highly abundant. Looking at fruitflies in which the piRNA pathway is inactive and transposons are therefore freely expressed, the scientists found copia in female flies in a seemingly dead end, namely the abundant germ line nuclei that will not become the oocyte’s genetic material and, thus, are destined to undergo programmed cell death.

In male flies, however, copia retrotransposons move from the cytoplasm to the gamete nucleus during spermatogenesis, indicating that nuclear entry could be an essential part of its replication cycle tailored to the element’s niche—the male testes.

“Transposons were long overlooked as junk DNA but have a broad impact on their host’s biology and evolution. Our study demonstrates the power of cryo-ET for studying the cellular structural biology of transposons and obtaining detailed insights into the cell biological mechanisms underlying their replication cycles,” Klumpe says.

Provided by Institut für Molekulare Biotechnologie der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften GmbH