All roads lead to fibrosis, at least when it comes to chronic inflammation. The condition can occur almost anywhere in the body where inflammation is present, driven by the abnormal growth of activated fibroblasts—collagen-secreting cells found in connective tissue—which build up in organs, hardening them.

Generally, fibrosis can be slowed but not stopped once it starts, meaning patients have only palliative treatment options until the organ must be replaced. Scientists working on improved treatments must figure out how to destroy profibrotic fibroblasts while leaving others, which are part of healthy tissues and involved in wound healing, intact.

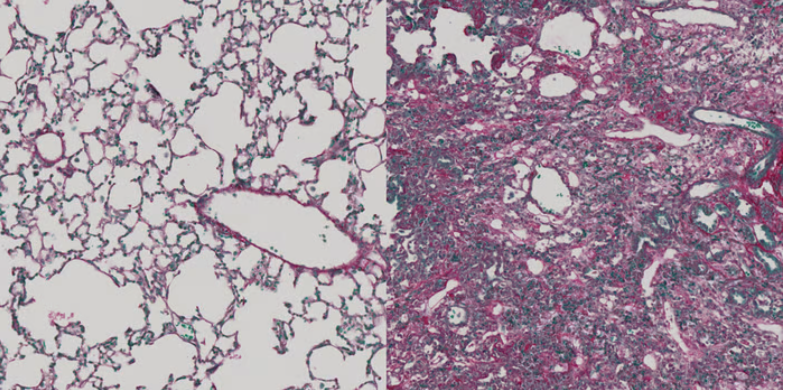

Now, a research team led by scientists from Switzerland’s University of Zurich may have done just that, at least in mice. In a study published Thursday in Cell Stem Cell, they reported that immunotherapies separately targeting two peptides expressed only on fibrotic fibroblasts with cytotoxic T cells reduced liver and lung fibrosis in mouse models without damaging healthy tissue or processes.

“With the newly developed immunotherapy, we were able to eliminate fibroblasts efficiently in mice, thus reducing fibrosis in the liver and lungs,” Christian Stockmann, M.D., the study’s head researcher, said in a press release.

The researchers developed their hypothesis around earlier studies showing that chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells could effectively target fibroblasts in mouse models of cardiac and liver fibrosis as well as progress on the use of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells to recognize and destroy tumor-specific antigens. With this work in mind, they wondered whether there were specific self-peptides on the surface of fibrogenic cells that T cells could target, similar to how they are targeted in cancer immunotherapies.

To find out, the team used a software program to examine the surface proteins of activated and non-activated fibroblasts. They identified two potential targets: ADAM12 in liver tissue and GLI1 in the lungs, which were present on the activated cells but not the nonactivated ones. Immunofluorescent staining of mouse and human cells confirmed their findings.

Next, the scientists used lentiviral vectors to develop two separate vaccines that would direct cytotoxic CD8+ T cells to attack cells expressing ADAM12 and GLI1. The vaccine targeting ADAM12 reduced established liver fibrosis in mice and prevented fibrosis from forming. It also improved liver function in mice who already had the condition, as evidenced by protein markers associated with healthy liver tissue. Moreover, immunization against ADAM12 or GLI1 prevented fibrosis in the lungs of mice who received the vaccine prophylactically.

To ensure that the immunotherapies didn’t damage healthy tissue, the scientists conducted a series of studies on vaccinated mice to check the integrity of the skin, heart, muscle and other organs, along with blood tests to look for markers of damage. In all cases, the tissue remained healthy. The same was true for wound healing, which was studied in mice with skin and tendon injuries.

“This suggests that our immunization approach to target fibrogenic cells does not have severe adverse effects with regard to the homeostasis and microarchitecture of major organs or physiological healing responses,” the scientists wrote.

Whether the results will hold up in humans remains to be seen. As the researchers note in the paper, ADAM12 is expressed in the male reproductive organs and female placenta during pregnancy, presenting the potential for serious complications in the minority of fibrosis patients who are in their reproductive years. It’s also not clear how durable the immunotherapies will be; previous cancer studies have shown that multiple therapeutic vaccines are required to sustain T-cell reactivity.

For now, the researchers remain hopeful their work will translate to the clinic. They are in the process of studying suitable vaccination targets in humans, Stockmann told Fierce in an email.