Arsenal Bio is jumping headfirst into the cell therapy arena, and its latest fundraising haul, backed in part by Bristol Myers Squibb, is making a significant splash.

The company has reeled in $220 million in series B cash—one of the largest single hauls of 2022—off the promise of its fine-tuned, gene-edited cell therapies. With this money, Arsenal has raised more than $300 million in less than three years. Backed in part by BMS, the fundraising round unveiled Tuesday, Sept. 6 will pay for more staff and push the company’s early programs toward the clinic, led by Arsenal’s lead asset AB-1015.

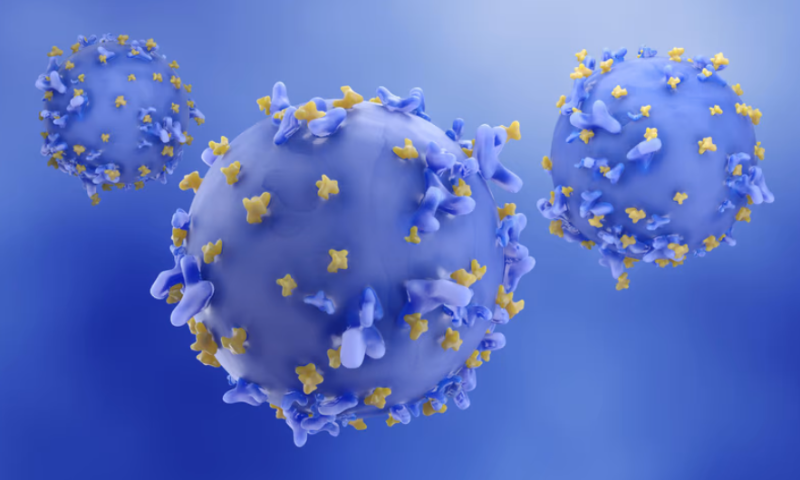

In an exclusive interview with Fierce Biotech, Arsenal CEO Ken Drazan boiled down the company’s business strategy into three prongs: develop nonviral, gene-edited, autologous T cells to treat solid tumors; build a robust database of instructions for figuring out how best to edit these cells; and partner up with other companies.

“The reason I say that is because there are over 200 cancers; Arsenal can’t possibly develop treatments for all of them,” said Drazan. “And if our technology is truly enabling that way, we’d like to create a business model that enables partners to develop medicines for other cancers that we’re not pursuing.”

This approach has already been put to the test via the company’s collaboration with BMS, made back in January last year. In exchange for $70 million in upfront cash plus milestone payments, Arsenal agreed to discover and build “preclinical candidates against multiple targets.” BMS also agreed to invest an undisclosed amount in the company. The deal was extended a year later, with BMS adding an additional candidate for an undisclosed milestone payment.

“It’s a growing relationship, and we expect to try to use this capability to work with other biopharmas across the world to tell that mission,” said Drazan.

Differentiating Arsenal from others in the field, according to Drazan, is its ability to edit genes without viral vectors, which have different integration sites for each cell being tweaked. Instead, the company targets chromosome 11, which Drazan says is a “safe harbor.”

“It’s far away from any other critical gene in the genome, including the ones that are expressed in T cells,” he said. “When we use our manufacturing process, it means that every single cell in the bag has the exact same integration site.” Arsenal also utilizes logic gate technology, which, simply put, enables more precise delivery of treatment and minimizes off-target hits and, thus, side effects.

Still, a different segment of the cell therapy industry is trying to develop allogeneic therapies—cells sourced from donors instead of a patient. Generally speaking, such treatments sacrifice treatment durability for simpler manufacturing and increased accessibility. But Drazan doesn’t want to sacrifice durability and feels that Arsenal’s planned manufacturing process has the potential to be administered more simply.

“We feel that with our synthetic technology that creates higher specificity, more set of programmable functions, that we can get to lower doses and an outpatient opportunity, potentially eliminating lymphodepletion,” he said. Currently, the company has a nine-day manufacturing time for its reprogrammed cells.

The promise of the company’s platform will soon be put to the test, with the company potentially asking regulators to launch into phase 1 with its lead asset, AB-1015, in a matter of weeks. The treatment is currently slated for ovarian cancer, with the company’s second and third assets targeting kidney cancer and prostate cancer, respectively. Drazan plans on those two programs being clinical trial-ready in early 2024 and early 2025.

As the company sets its sites on the clinic, Drazan underscored his commitment to recruit as diverse a trial as possible. He touted the makeup of Arsenal—60% of employees organizationwide are non-white—as evidence of this work. The latest report (PDF) from BIO, an industry trade group, found that among 28 responding companies, non-white employees made up 38% of the workforce.

“We are trying to find institutions that treat women with ovarian cancer from as diverse a background as possible,” he said. “So we place a high priority on it.”