Evidence is growing that insulin resistance drives Alzheimer’s disease development, and several medications used to treat diabetes are in clinical trials to see whether they can combat the condition. Now, new findings about the way insulin is delivered to the brain suggest it’s worth looking into a broader range of diabetes drugs than previously thought.

In a study published Oct. 25 in Brain, scientists from Laval University in Canada and Rush University Medical Center reported that they discovered insulin receptors on cerebral microvessels outside the brain’s hard-to-permeate central vasculature, known as the blood-brain barrier. This means drugs would not have to cross it to reach the receptors, widening the list of potential Alzheimer’s therapies.

“Before this study, the accepted view was that insulin crossed the blood-brain barrier to act mainly on neurons and astrocytes,” Professor Frederic Calon, Ph.D., co-corresponding author, told Fierce in an email. “We were surprised to detect that only a very small amount of insulin is actually transported across the blood-brain barrier.”

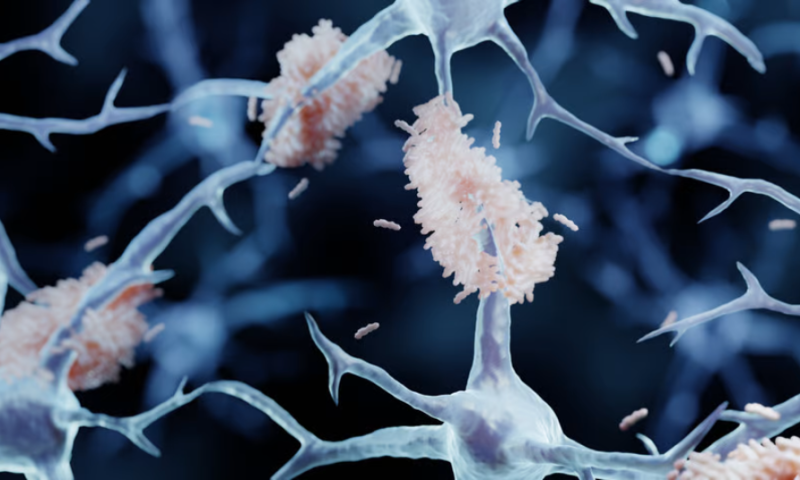

The scientists identified the receptors by analyzing brain tissue from 60 deceased individuals who had enrolled in the Religious Orders Study, which followed 1,100 priests, nuns and other clergy members for up to 22 years to better understand how aging affects cognition. In addition to finding that insulin receptors in the brain were primarily found in microvessels—not directly in neurons, as previously thought—the researchers also noticed that there were fewer of the alpha-beta insulin receptor type in the brains of subjects who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. The fewer of those receptors, the more Alzheimer’s-associated amyloid plaques accumulated in their brains—and the worse the subject had scored on cognitive tests during their lifetime.

To elucidate what was happening to the insulin receptors, the scientists conducted a series of studies on mice that were genetically inclined to develop a condition similar to Alzheimer’s dementia. First, they confirmed that the microvessels in their brains contained alpha-beta insulin receptors and that these receptors responded to circulating insulin without it having to cross into the blood-brain barrier.

Further experiments found that as the mice aged, the Alzheimer’s models had increasingly fewer alpha-beta insulin receptors than controls. They also had greater expression of the enzyme BACE1, which drives the production of amyloid plaque. Previous studies had shown that BACE1 activity contributes to the development of insulin resistance in the muscles and liver and that higher levels of it in the brain’s blood vessels are associated with cognitive impairment.

The scientists also found an inverse relationship between BACE1 levels and the number of alpha-beta insulin receptors, along with greater accumulation of amyloid plaque.

Together, the data suggest that BACE1 contributes to cerebral insulin resistance in the brain and Alzheimer’s pathology. While BACE1 inhibitors to prevent or treat Alzheimer’s have reached late-stage clinical trials in the past, they have failed to show efficacy or proved too toxic.

To Calon and his team, the new research is more evidence that the condition could be tackled by drugs for diabetes—an even wider swath of them than before, now that it’s clear that they won’t need to cross the blood-brain barrier to reach cerebral insulin receptors. “There is already a wave of drugs acting on insulin resistance that are being tested in Alzheimer’s,” Calon said. “I believe our results further justify trials with GLP-1 receptor agonists, for instance. There are also [combination] GLP-1/GIP agonists that look promising.”

Both GLP-1 receptor agonists and combination GLP-1/GIP receptor agonists have indeed received attention in recent years as potential agents against Alzheimer’s. The drugs work by stimulating insulin release from pancreatic islet cells, thereby increasing insulin sensitivity. Novo Nordisk’s semaglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, is among the drugs being studied for Alzheimer’s. Semaglutide is sold in the U.S. under the brand name Ozempic for diabetes and as Wegovy for weight loss in obese and overweight people.

Calon and the team hope their findings will encourage more clinical trials. In the meantime, they also plan to study what happens downstream of when insulin binds to the receptors on the microvessels.