Businesses are eager to hire, but they can’t find enough workers to fill record job openings

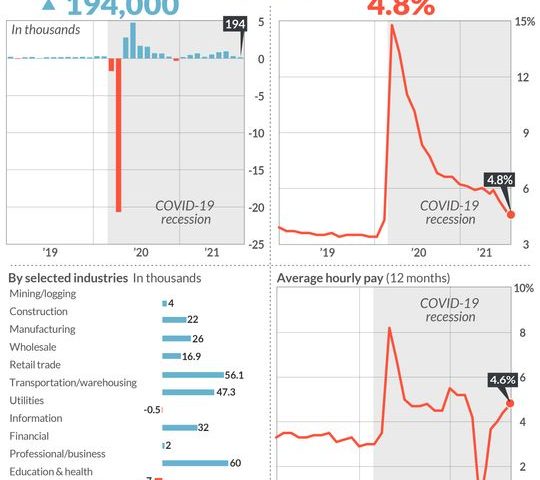

The numbers: The economy created a stingy 194,000 new jobs in September to mark the second disappointing monthly increase in a row, suggesting a lack of labor could frustrate a robust U.S. economic recovery in the months ahead.

The increase in hiring fell well short of Wall Street’s forecast, exacerbated by a decline in employment at public schools. Economists polled by The Wall Street Journal had forecast 500,000 new jobs.

The private sector added 317,000 workers last month, but state and local employment fell by 123,000.

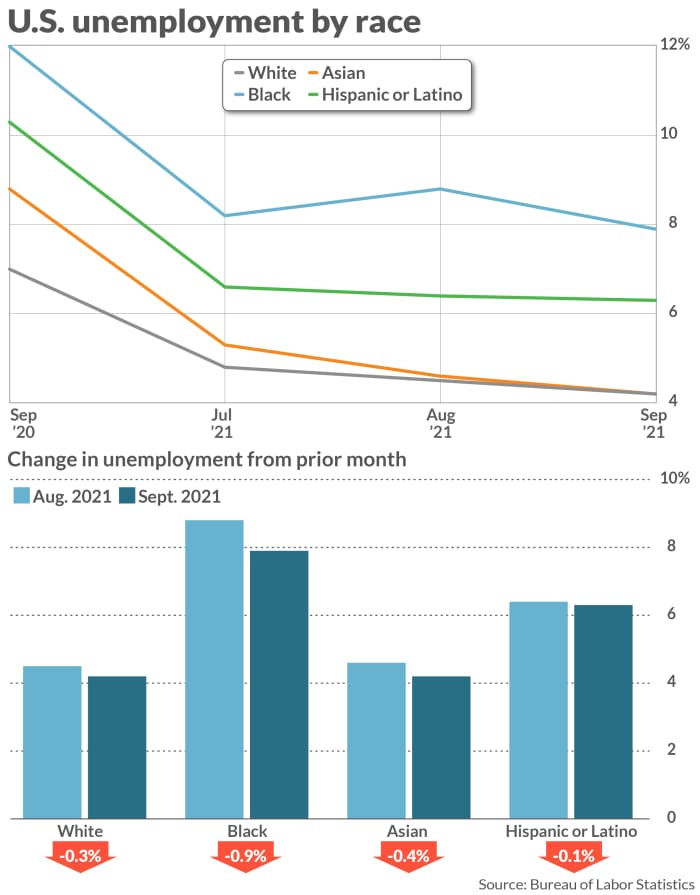

The unemployment rate, meanwhile, slipped to 4.8% from 5.2% and touched a new pandemic low.

The jobless rate for Blacks sank almost a full percentage point to 7.9%, accounting for much of the decline.

Yet the official rate underestimates the true unemployment by a few percentage points, economists estimate.

What’s worse, the size of the labor force actually shrank by 183,000 in September and partly explains the large drop in the level of unemployment.

The percentage of people in the labor force fell a tick to 61.6%, leaving it almost 2 points below its pre-crisis peak.

One of the biggest problems the economy faces right now is enticing enough people to return to work. Many businesses lack sufficient staff to produce enough goods and services to keep up with demand.

The tepid September jobs report adds to growing evidence the recovery has slowed, but it probably won’t deter the Federal Reserve from announcing plans soon to start to wean the economy off its easy-money strategy.

U.S. stocks rose in early Friday trading.

Big picture: The speed of the economic recovery could depend largely on many workers rejoin the labor force in the coming months.

Record U.S. job openings show there’s plenty of demand for labor. And with delta starting to fade, even more companies might be willing to add staff.

“There is no shortage of labor demand. Companies want to hire,” said senior economist Will Compernolle of FHN Financial Markets.

The problem is, the labor force is missing as many as 6 million people who likely would be working now had there never been a pandemic at all.

What might nudge more people to return to the labor force soon are the end of extra federal benefits for the unemployed and most schools reopening for in-person learning. But it will take several months to see if they are coming back — and how quickly.

Key details: Employment grew the fastest last month at businesses in leisure and hospitality that have shown the most sensitivity to the coronavirus. Hotels, theaters and the like generated 74,000 new jobs.

Yet that’s just one-fifth of the average increase in industry employment during the spring, suggesting the late-summer surge in coronavirus delta cases held back hiring in September.

Employment increased by 60,000 at white-collar professional businesses, 56,000 at retailers and 47,000 at transportation companies that deliver goods to customers.

The number of new jobs also rose modestly in manufacturing and construction.

The only sector to report notably lower employment was government, mostly in public education. The decline in school employment reflects quirks in seasonal hiring tied to the pandemic instead of broader problems with the economy.

By and large, the economy has expanding quite rapidly, but the shortage of labor threatens to put the U.S. on a slower growth track and feed the biggest increase in inflation in 30 years. Most businesses are raising wages to try to lure workers or poach them from rivals.

Average pay rose 19 cents to $30.85 an hour, pushing the increase over the past year up to 4.6% from 4%. Before the pandemic wages were increasing at a more leisurely 3% a year.

Yet higher inflation is eating up most if not all of those wage gains.

Prices have jumped 5.3% over the past year using the better known consumer price index. And the are up 4.3% in the last 12 months using the Fed’s preferred personal consumption expenditure inflation gauge.

Another step businesses have taken to cope with the labor shortage is to increase overtime hours.

The average number of hours Americans work rose two tenths of a percentage point to 34.8 hours a week. Before the pandemic the length of the workweek had never gotten so high.

Hiring in August, meanwhile, was not quite as weak as it originally seemed.

The government revised its estimate of how many new jobs were created to 332,000 from 235,000. That’s still well below the average increase during the spring, however.

What they are saying? “Labor demand remains robust, but a combination of factors continues to limit stronger job creation,” said Jim Baird, chief investment officer at Plante Moran Financial Advisors.

“Hopefully the current decline in Covid case counts continues,” said Indeed Hiring Labs director Nick Bunker. “That seems to be the only way out of our current situation.”

Market reaction: The Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, -0.03% and S&P500 SPX, -0.19% rose slightly in Friday trades after an up-and-down start to the trading day.