With 40 million people thought to suffer from dementia throughout the world and the number due to double in 20 years, there’s no overstating the desperate need for drugs to slow down its progression.

And unfortunately, there’s no overstating the amount of money spent in pursuit of an Alzheimer’s disease (AD) therapy that addresses its underlying processes—to little practical effect so far.

Alzheimer’s accounts for the bulk of dementia cases, and for decades the only available treatments were drugs that try to restore neurotransmitter levels in the brain, which only affect symptoms and have modest effects at best. The last of those was approved 17 years ago.

Billions of research dollars have gone into discovering the underlying mechanisms in AD and seeking drugs that can disrupt the pathogenic steps that lead to the destruction of neurons, but it’s a hugely long and expensive process.

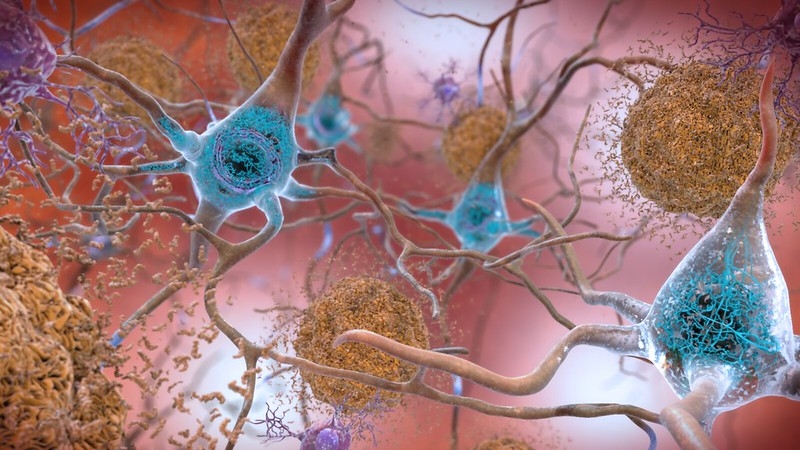

For many years, researchers have concentrated—one might even say fixated—on the physical manifestations of AD visible in the brain, namely extracellular amyloid plaques and, more recently, intracellular tau protein tangles.

That has been a largely thankless task with well over 200 failed programs, many of which advanced to the costly phase 3 testing stage before being abandoned—although one amyloid drug once left for dead was revived last year and submitted to the FDA this summer (more on that later).

Despite the attrition rate, amyloid-targeting drugs still account for 13 of 32 candidates in late-stage clinical trials in AD—around 40%—just about the same percentage as the year prior, according to an analysis (PDF) from the Us Against Alzheimer’s organization presented at this year’s Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

The remaining 19 are split among several other approaches, from tau-targeting attempts to a mixed bag of other drugs aimed at protecting neurons from degenerating and blocking inflammation and metabolic processes linked to dementia.

The shift from amyloid more apparent in the mid-stage pipeline, however, where nine of 58 programs are now targeting that protein and the rest are spread into other approaches. Fifteen, for instance, fall into the neurotransmission category, and just six are targeting tau.

The Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation is convinced that the answer to treating AD will lie in using multiple drugs in combination, or drugs with multiple effects in one molecule, reflecting the fact that it is an enormously complex disease with multiple causes and pathologies. Understanding AD is made even harder by the fact that the disease can be definitively diagnosed only post-mortem, by examining the brain.

It’s also worth noting that many of the predictions and timelines in this article predate the coronavirus pandemic, so may be overly-ambitious if the disruption caused by COVID-19 extends for months more. Many of the readouts are due between now and 2022, so one thing’s for sure—there’ll be plenty of news in AD over the next couple of years.