Air pollution in capital territory 20 times higher than WHO recommended safe level

The residents of Delhi have already begun to forget what it is like to wake up and see the sky.

Almost a week on from Diwali, the thick brown smog that shrouded the city after the festival has showed no sign of shifting. On Friday, as the air became poison and 20 million people struggled to breathe, a public health emergency was declared, with Delhi’s chief minister Arvind Kejriwal declaring the city had turned into a “gas chamber”.

Sachin Mathur, 31, an auto rickshaw driver in north-west Delhi, said he was forced to stay outside for work but had been struggling to breathe as he went about his day, and could barely keep his eyes open on the roads because the pollution made his eyes tear and sting.

“I have been driving auto on Delhi roads for last three years and every year this time after Diwali Delhi becomes like this,” Mathur said. “I am suffering from a throat infection and my eyes are burning. The pollution means I do not get many passengers, so going to a doctor is not affordable.”

The air pollution crisis is now an annual tradition in Delhi at this time of year, thanks to a toxic mixture of smoke from celebration firecrackers combined with the farmers in the neighbouring regions of Punjab and Haryana burning their crop stubble and a cold shift in the temperature locking in the fumes.

But despite promises that new laws and regulations, including the banning of firecrackers, would keep the air cleaner, the air quality index soared to above 500 this week, levels 20 times higher than those deemed healthy by the World Health Organization.

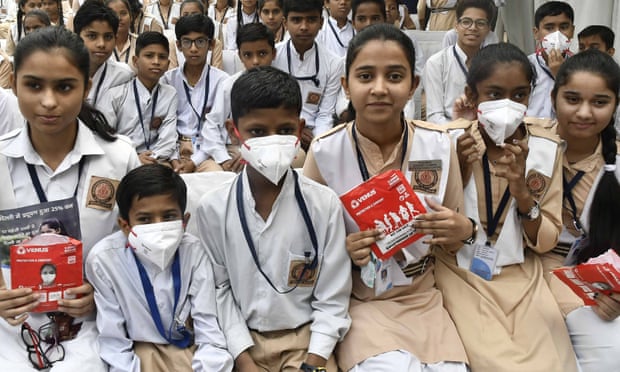

The schools have now been closed until Tuesday, all construction has been ordered to stop and the government has organised for 5m masks to be handed out. From Monday the city will also begin a trial run of a scheme in which cars with odd and even numbered licence plates drive on alternate days. But many in the city said far stronger measures were needed, particularly to stop the main pollution culprit, crop-burning fumes from neighbouring states.

Rachel Rao, the vice-principal of Queen Mary’s school in Delhi, said they had been forced to limit outdoor activities for those in the school. “Over the past 10 years the situation has been getting worse, we never used to see pollution like this,” said Rao. “The past few days have been absolutely awful. We have seen many of our pupils falling sick and complaining of having difficulty breathing.

“Before Diwali, we tried to spread awareness among our students about not burning firecrackers, in the hope they would bring that message back home. But the Delhi government, the Punjab government, the Haryana government and the central government should be coming up with better solutions rather than just blaming each other for the problem.”

Neeraj Sharma, 45, a businessman, said his 16-year-old son was a professional athlete but he had been forced to stop his training this week because the pollution levels made it impossible to exercise.

“It is very difficult to breathe in this weather, there is a bitter taste in the air,” said Sharma. “I think the government is very superficial in their approach to pollution control. For the last five years the Delhi government did nothing, but now, as an election is approaching, they are acting as if they are concerned. The Delhi government said they banned crackers in Delhi, so how come so many of them were bursting all over Delhi during Diwali?”

Sharma sighed deeply. “If you ask me, nothing will change, the situation will continue to go from bad to worse.”

Hospitals in the capital reported a upsurge this week in patients coming in with respiratory issues. Dr Sai Kiran Chaudhary, the head of pulmonology at the Delhi Heart & Lung Institute hospital, said people had become much more aware about the dangers of pollution in the past two years, with masks becoming a common site in the city this week and people staying indoors. “Everything, from increased construction, increased urbanisation, increased construction, increased number of cars on the road, and a reduction of green spaces, is making this problem worse every year,” said Chaudhary. “So many people are losing their lives.”

Indeed, the long-term health implications of living with this air was laid bare in a study by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago, released on Thursday, which found that the life expectancy of people living in the Indian states of Bihar, Chandigarh, Delhi, Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal has reduced by up to seven years due to pollution.