Scientists head to Weddell Sea to model changes to the shelf since the calving, in 2017, of the massive iceberg A68

In the comings days, a team of scientists, technicians and other specialists will gather onboard the SA Agulhas II, a 13,500-tonne ice-breaker moored off the coast of Antarctica, and make final preparations for one of the most ambitious polar expeditions in decades.

Guided by satellite imagery and drones flown from the research ship, the vessel will set off on New Year’s day through the pack ice of the Weddell Sea, part of the Southern Ocean in the Antarctic. The ship’s destination is the Larsen C ice shelf where a trillion tonne iceberg, four times the size of Greater London, calved away in July 2017.

Antarctica has a way of dashing even the best laid plans. But if the Weddell Sea expedition can reach the Larsen C ice shelf, the fourth largest on the continent, the researchers will have an unprecedented chance to study how it and others like it melt, fracture and collapse, and what life ekes out an existence in the sheltered waters beneath.

But there is more to the expedition than science. The Weddell Sea is infamous in Antarctic history as the place where, in 1915, Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance became trapped in ice for 10 months. The crushed vessel finally sank in more than two miles of water.

One the way home, pack ice permitting, the Agulhas will head for the spot where Endurance went down and, for the first time, hunt for the wreckage with autonomous robotic submarines.

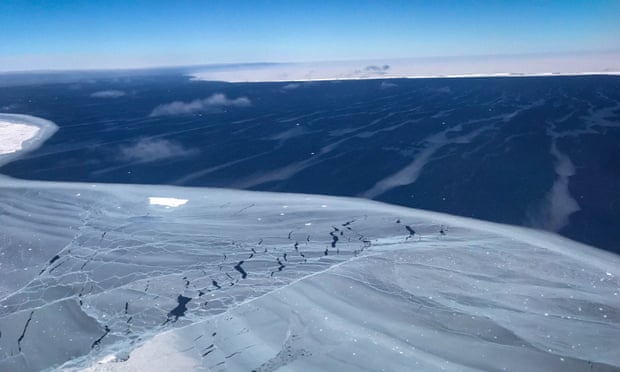

View at the Larsen C ice shelf looking out to the 600ft thick giant iceberg A68.

“Antarctica is a place of extremes. You never know what the conditions will be like,” said Julian Dowdeswell, director of the Scott Polar Research Institute, in Cambridge, and chief scientist on the Weddell Sea expedition. “But if we are that close to one of the most iconic vessels in polar exploration, we have got to go and look for it.”

So far, satellite images of the Weddell Sea show that ice coverage is low for the time of year, tipping the odds in favour of the Agulhas reaching its goal. The massive iceberg, known as A68, which broke off the Larsen C ice shelf is helping out too. There is a clockwise gyre in the Weddell Sea that brings sea ice west and north, but the iceberg has swung out to block the flow, leaving the northern waters clearer for expedition’s approach.

If the expedition reaches the Larsen C ice shelf, researchers will launch two autonomous robotic submarines which will dive under the ice and map the shelf with upward-looking sonar. Scientists will look out for cavities in the underside of the ice, created when the relatively warm sea water melts the shelf from beneath. Coupled with measurements of sea temperature and salinity, the data will be fed into computer models showing ice shelf melt, fracture and collapse.

Ice shelves form when inland glaciers bearing ice that has built up over thousands of years reach the coast and extend over the water. Some can go hundreds of miles offshore. Because ice shelves themselves are floating, sea levels are not directly affected when they melt or collapse. Instead, the ice shelves act as buttresses and when they disintegrate the glaciers on the land flow more quickly into the sea. The glaciers held at bay by the Larsen C ice shelf contain enough ice to raise global sea levels by about 10cm.

The robotic submarines will also map the seabed under the ice shelf with downward-looking sonar. If the Larsen C ice shelf has disintegrated before as part of a natural cycle of growth and collapse, researchers should find scars called “ploughmarks” on the seafloor, created as the icebergs are dragged around by ocean currents. No ploughmarks will be bad news: it will suggest that the recent breakup of the Larsen C shelf is unprecedented over the past 20,000 years.

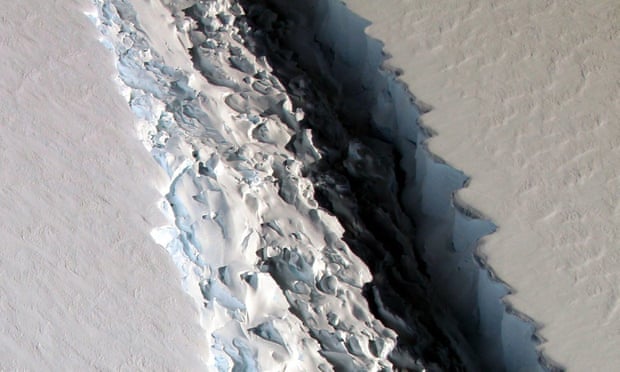

Nasa photograph showing a massive rift in the Antarctic’s Larsen C ice shelf, on 10 November 2016.

The east coast of the Antarctic peninsula once had four main ice shelves, named Larsen A, B, C and D. The Larsen A and B shelves collapsed in weeks during 1995 and 2002 respectively. “With those already gone and with A68 cleaving off Larsen C, there is a concern something similar may happen there,” said John Shears, the expedition’s voyage leader. “It could be a precursor for something big.”

If the seafloor is clear of the huge boulders that glaciers have a habit of dragging to the sea, the robotic submarines will dive down and film the sea bed for the biologists on the expedition. The submarines may spot starfish, brittle stars, corals and sponges, and perhaps the odd passing toothfish.

Lucy Woodall, lead biologist on the expedition and principal scientist at the Nekton Oxford Deep Ocean Research Institute, whose mission is to explore and conserve the ocean, said: “We have so little information about anything that is living on the seafloor, or under the sea ice, that every bit of biology is going to be interesting to us. It is easy to think the days of exploration are over – and they sort of are in the terrestrial world, but in the marine world they still very much exist.”

On the home leg of the 45-day expedition, the team will decide whether to look for Shackleton’s lost Endurance. The Agulhas will probably have to break ice for several days to reach the spot where the doomed ship sank. If they get there the water has to be clear enough to launch the robotic submarines without risk of losing them.

“We’d love to get to the wreck site, but it’ll be a challenge even in a light ice year,” said Shears. “No one has ever got close. If it was easy to do someone would have done it a long time ago.”

Dowdeswell is confident that if they can only find a route through the ice the vessel will be theirs to discover. “If we can get there with the ship we have quite a good chance of finding the Endurance. It would be the most memorable event in my career.”